Whistle While You Work

If, like me, you have too much free time on your hands, you have probably wondered why Snow White, at least as Walt Disney portrays her tale, has small woodland animals to help her with her household chores, with bunnies and chipmunks scrubbing dishes, songbirds helping to sew and fawns dusting the furniture with their white tails.

If, like me, you have too much education on your hands, you probably have used Aristotelian categories to analyze the question.

If, as a child, you ever asked the question “But WHY must I go to bed?—I am not sleepy!” and heard the answer, “Because Daddy says so!” and you found the answer unsatisfying, you experienced the frustration of hearing the wrong kind of answer to the right kind of question.

The sleepy child is asking for a justification, asking what fair purpose light’s out for unsleepy children serves, and the impatient parent is explaining a formality, that a command from a lawful authority must be obeyed independent of its fairness. It answers a different “why” than the “why” that was asked.

Aristotle answers that there are four kinds of answer to the question “why.”

- Final cause is motive, or, in other words, it is the answer in terms of that for the sake of which the thing is done to explain the thing.

- Formal cause is structure, or, in other words, it is the answer in terms of how the thing is put together, the relation of parts one to another, to explain the thing.

- Material cause is substance, or, in other words, it is the answer in terms of the content, what stuff the thing is, to explain the thing.

- Efficient cause is the past, or in other words, it is the answer in terms of the mechanics of cause and effect leading up to the thing being asked.

In this case, we can discard the answer that “Snow White has maidservant bunnies because Uncle Walt put them in the story” – this tells us the efficient cause, and we don’t care about that.

Likewise, we can dismiss the answer that “Snow White has maidservant bunnies because it is a fairytale and therefore made of make-believe: in real life, when I tried to get my bunny to clean the rug, he left poop pellets over everything, and ate the leather slip covers on my couch” — this tells us that you never want to ask me for advice on housekeeping or animal-training.

Likewise again, to answer that “Snow White has maidservant bunnies because they are a convenient labor-saving pets for her” gives the story-world final cause, that is, it tells us Snow White’s motive inside the story; but it does not tell us the real-world final cause, that is, it does not tell us Walt Disney’s motive outside the story.

Presumably the motive of Uncle Walt is to tell a good and memorable and charming story to entertain both young and young-at-heart. That we can presume, but it does not answer the question asked.

In this case, the answer we are asking is one of formal cause, that is, what makes this particular conceit entertaining, that is, charming and memorable and good?

We want to know what about having shy and wild deer befriend and love a virginal maiden appeals to any audience whose hearts are fit for fairy tales. We want to know what about furry animals doing human chores appeals to those young children and graybeard philosophers innocent or wise enough to delight in fairy stories.

Snow White and her Cleaning Crew

The alert reader will note that I introduce a thought into this question slyly, but, if I may be allowed, crucially. I propose that we cannot answer what makes a story element fit for being told in a fairy story without answering what makes a heart fit for hearing a fairy story.

Let us answer the smaller half of the question first, as it is easier. I assume nearly everyone who likes fairy stories likes seeing wild animals befriend the virgin princess in the story sees immediately what the appeal is. Any reader who cannot see it is asked merely to imagine the same conceit in other types of tales, so as to see how wrong or comical it would be there.

Imagine the detective story where the hard-boiled gumshoe, having just survived a beating from Kineno, the thug of Eddie Mars the gambler, and only now realizing that his old pal Sean Reagan whom everyone thinks ran off with Eddie’s wife to Mexico is actually dead, stumbles into his ratty apartment lit only by slanting strips of light from the venetian blinds. A cigarette is dangling from his bleeding lip, and hatred glinting from his swollen black eyes. He stumbles over to his gun cabinet, and his pet groundhog, Mr. Flunbuffly, hands him a tumbler of scotch. Dwinky the Fawn reloads his shooting iron for him.

Such a scene could be done for comical effect, or absurd, or as a wild hallucination after a svelte dame slips someone a Mickey, but it is foreign to the mood of film Noir whodunits and utterly outside the conceptual frame of what a detective story universe allows.

To use a less absurd example, imagine a similar scene either in a sword-and-sorcery story, or a myth, or a work of science fiction or high fantasy.

Conan and his Fox

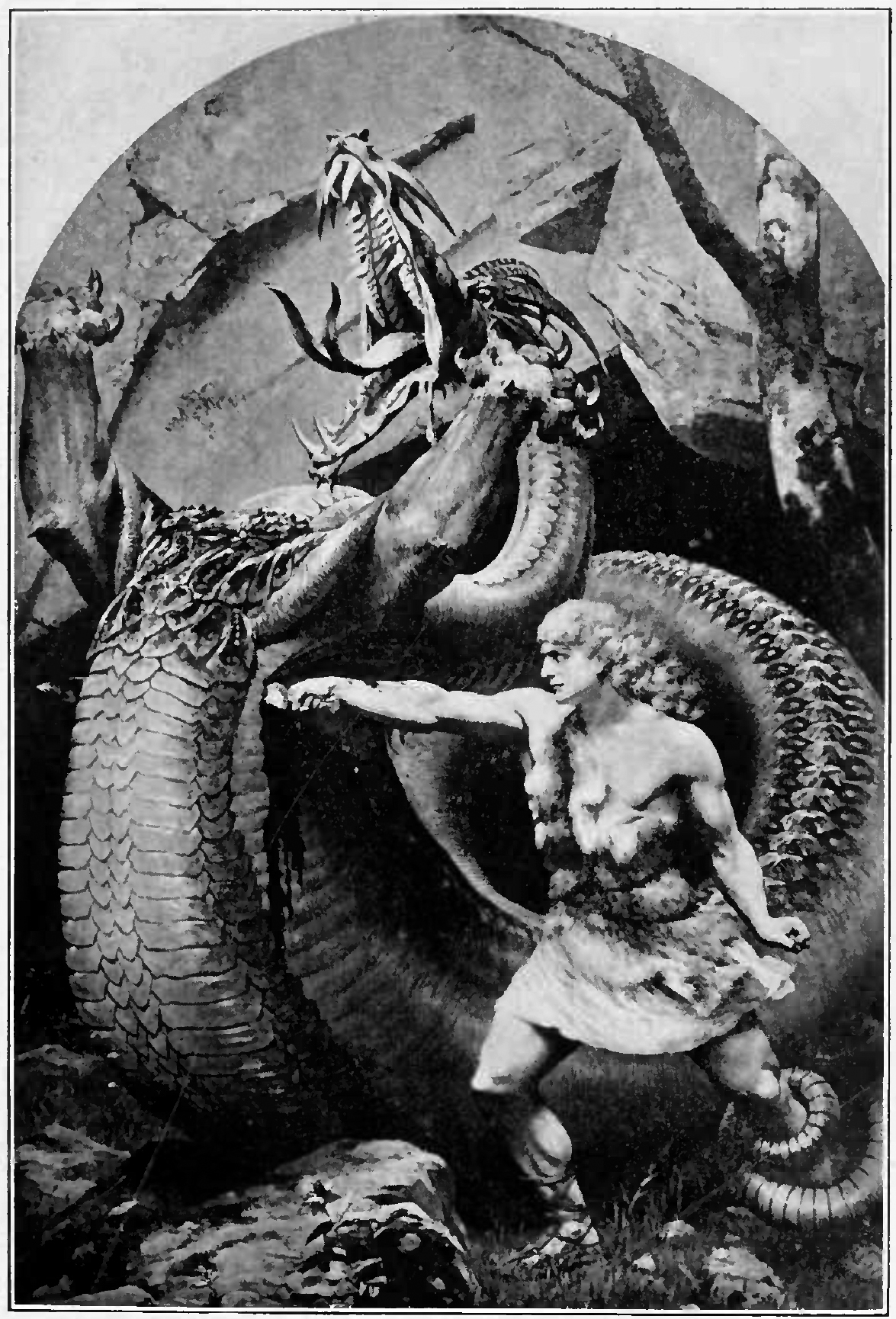

Conan the Barbarian we can imagine strangling a vulture with his teeth while being crucified, because he is the baddest of badasses ever to tread the bloodstained pages of pulp magazines. We cannot imagine Blinknose the Beaver sharpening the sword of his fathers before sending him with a few words of sage advice to face the snake-god of Stygia in the windowless and primordial temple from which the smokes of incense and the screams of victims on moonlight midnights arise.

If the veil between man and nature is ever parted for Conan, and this applies to all the Sword and Sorcery I have read, what comes through the parted veil is a monster, an abomination stirred up by the aforementioned sorcery, something to be slain with the aforementioned sword. Conan dwells in a Lovecraftian universe, where the things beyond mortal ken are hostile, unearthly, indifferent, and they do not want to talk to you.

Cthulhu does not want to be your friend.

The Great Old Ones in this respect are more horrible than the Mephistopheles of Faust. They do not want to tempt you, and will make no bargain, signed in blood or no, for your soul.

Now, I am not saying all Sword and Sorcery is Lovecraftian, but I am saying the sorcery is more often Eldritch than it is Disney. I don’t think I ever read a single tale of this kind where Elric of Melnibone or Solomon Kane had his fairy godmother turn a comedy relief mouse into a steed for him to ride to war. It is not the kind of thing Arioch, Lord of Chaos, does for you.

Siegfried discussing matters with Fafnir

But note that Siegfried from the Wagner opera seems to have as many animal friends as Snow White. He plays with a bear that terrifies his foster father, Mim the Dwarf, and he understands the speech of the songbird that warns him Mim means to murder him. A myth has some element sword-and-sorcery is lacking. The common thread here is that Siegfried is like Tarzan or like Romulus and Remus, a man both closer to nature than any civilized man, but also possessed of a glamor or a power due to this innocence.

But note that the opposite of Snow White is seen in these Noble Savages: Siegfried is stronger than the bear, and can play with him as if with a puppy, in rough friendship, but in no way does he domesticate the bear, or set him to cooking or cleaning or sweeping, or even helping him to forge a sword.

Science fiction differs from fantasy and fairytales in one special conceit: the magic and the wonder in science fiction is confined to those which can be fit into a naturalistic universe, one where only those mysteries of the universe that can be discovered by science are real.

Now, this might not seem like a deep difference. After all, we might ask, what is the difference between a dragon from planet Pern or Velantia and a dragon from the Lonely Mountain or from Neidhöle? What is the difference between a Slan or Lensman or Vulcan who reads minds and an Elf-Queen who reads hearts? What is the difference between the Time Traveler who visits the Morlocks of AD 807901 and Ebenezer Scrooge who visits the graveyard in a Christmas of some future year closer at hand?

To travel in time or read minds or deal with dragons are alike in that they are wonders and mysteries, things we cannot do in real life. But the difference is clear and deep: the flying lizard creatures of Pern are extraterrestrials. Fafnir of Neidhöle is supernatural. What Slans or Lensmen or Vulcans do, according to the rules of their own make believe universe, is a natural effect, either a skill that can be learned, or a native talent no more supernatural than an electric eel’s ability to discharge a shock. The Time Traveler built a time traveling machine, which any competent workman with the Time Traveler’s blueprints and materials could duplicate. It is just as impossible as a radio would have been in the Bronze Age. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a ghost, a spirit, something science cannot explain nor science worshipers admit possible.

If the Gray Lensman came back to his barracks from a hard campaign of blasting Boskonian space-pirates out the ether, he could not find a fuzzy animal mopping the floor or polishing his raygun. He could find an underperson or uplifted animal, of course, something from the island of Dr Moreau changed by science to be intelligent; or he could find any number of fuzzy extraterrestrials. Indeed, a suspiciously large number of extraterrestrials are our all-too-terrestrials fellow earthcritters merely propped up on their hind legs. Kzinti are cats, for example, and Selenites are termites.

Nice kitty!

Green Martians are Red Indians and Green Osnomians are Red Martians are who nudists, and Romulans are Romans, and Klingons are Russians unless later they are Samurai, and Vulcans are Houyhnhnms who are horses.

But in each case, if the story is science fiction and not fantasy, the reason why the talking animal talks is that some undiscovered but quite natural property of natural science allows for it, such as the natural evolutionary development of intelligence on extraterrestrial worlds.

A second difference is one of familiarity. A talking fox or a talking tree we can easily imagine to be like the trickster from PINOCCHIO or Treebeard from Tolkien. But a Martian is either a monster, something strange and dangerous, or an alien, someone strange whether dangerous or not. Possibly the Martian is a space princess named Dejah Thoris, who happily is both gorgeous and naked, but even she must be alien in the sense of exotic and alluring, if she is to be a convincing Martian.

There is a veil between the human world and the Otherworld in fairy tales which the tale penetrates, and we imagine what life is on the other side. In science fiction the veil is between the human world and other places in time and space and other dimensions, between the natural world we know and unknown worlds equally as natural as our own. They can be extraterrestrial and even extra-dimensional, but they cannot be literally uncanny nor, in sense that Elfland or Inferno is, can they be unearthly.

But now we are far afield, so let us quickly return to the point of the appeal of seeing a maiden befriending animals to do human tasks. I hope we are all agreed from the examples above, and many others we can imagine, that the appeal is a longing to be at peace with nature, to cross the gap which even those men who do not believe in the literal garden of Eden will admit exists. There is something in the human soul that longs for Arcadia, for the Golden Age of Saturn, for the time which modern science says never existed, but all myths report once did exist, when man and nature were one, and beasts were our brothers.

To be sure, there is many a modern myth, spun by Rousseau or Marx and seen in stories like DANCES WITH WOLVES, about the Edenic times when we were all noble savages. Some of these myths pretend to be scientific, but real science, studying the skull wounds of Neolithic corpses, can tell the murder rate back in the Stone Age was higher than anywhere in the modern world, and that includes inner cities during riots and provinces at war. It should rightly be called not the Stone Age but the Homicide by Stone Ax Age.

Whatever science or pseudoscience says, any one whose heart is fit to hear fairytales knows a sense of loneliness and loss which is soothed, but only in part, by sublime beauties of nature. There is something out there we all want to embrace, and to have it talk to us.

That, by the way, is the point of the appeal of having the fuzzy woodland friends do chores. If Snow White were seen keeping house for the dwarves, but what she did was get a cat to keep the rats out of the grainstore, go duckhunting with her faithful hound Greatheart, and hitch up a horse or ox to plough the field, or keep bees for their honey or chickens for their eggs or keep lambs for their veal, then the gap between man and nature is still in place, and the virgin has not lured the wild things over the gap to our side.

No doubt by now some readers are puzzled at my repeated use of the words virgin and maiden, and, if those readers went to public school instead of getting an education, they are not only puzzled but offended. This brings up a second and larger point about woodland creatures working at human tasks, which is, namely, what power does the fairytale virgin possess which enables her to overcome or ignore the gap between man and nature which afflicts the rest of the Sons of Adam?

It is, of course, her innocence. Much as it appalls the braindead zombies indoctrinated by public schools, innocence is better than the cynicism or shared guilt or victimology taught by modern thought, and, if we place faith in the account Moses told the Children of Israel about Eden, it was lack of innocence that drove the parents of mankind out of paradise.

Even more appalling to the zombies, the perfect symbol and image of innocence is virginity. That is a word that is not much in use these days, except perhaps as a badge of shame, for reasons too uncouth to mention in this article.

The odd thing is that even the modern cynics, provided they do not notice or do not admit to themselves what these symbols mean or which longings of sad human nature fairytales satisfy—the odd thing is that even they can have hearts fit to hear fairytales. What they cannot do is reconcile this with their head. They must compartmentalize and separate with thought-tight cells their love of fairytales with the empty and emptyheaded cynicism that passes for wisdom in this modern world.

In this regard, let us briefly touch on the masculine side of the question. Why is it that Siegfried and Mowgli and Tarzan have this same Disney Princess oneness with nature, but it has no domestic flavor to it, no sweetness and charm? To ask the question is to answer it: boys are different from girls, and it is only the modern mind, and the perversions encouraged by the modern mind both intellectual and sexual, which have the effrontery to say otherwise.

Where the innocent virgin princess lures nature across the gap of Eden to our side, and heals the primordial loneliness by making companions of the wild beasts, the noble savage prince rips off his shabby cloak of civilization, dons his leopard-skin loincloth, takes his knife between his teeth, and leaps across the gap to the savage side, clawing his way up via dangling vines and man-eating plants to the brink on that far side, there to wrestle apes and strangle lions. If you don’t get the difference, then you don’t understand what makes girls girlish and boys boyish.

Now, let me not be accused of saying that in imaginative tales the girls are cooperative with nature and boys are competitive. That is not what I am saying at all. Both sexes, merely because we all are human, are prone to that sorrow and loneliness which the contemplation of the beauty of nature soothes, in the same way looking at the photo of a distant loved one is soothing; but it also, like adoring a photo of a loved one, tempts and exasperates the same mood that it soothes. We still feel apart from nature.

The loneliness is not a desire for companionship alone. Dog owners and cat owners have an emotional rapport with their pets. The loneliness is a desire for camaraderie, that is, for speech and communion with other intelligences beside man.

I call it communion because there is more involved in this longing than merely interaction with nonhuman intelligences. In the earliest science fiction story I’ve read that star nonhumans, WAR OF THE WORLDS by H.G. Wells, the Martians are simply monsters. They do not speak and make no bargains with mankind any more than Cthulhu does. Their intelligence involves no community or common ground with man.

And, again, because Science Fiction is a naturalistic genre, one where supernatural events are foreign to the suppositions of the tale, often when is emphasized in a tale starring alien beings is precisely that they are alien. As John W Campbell Jr famously challenged his writers, a truly alien alien would be as smart as a man but not think like a man. For me, the best example of nonhuman intelligence in a story was in A MARTIAN ODYSSEY by Stanley Winebaum. Tweel the Martian has only limited communication with the human with whom he travels, and the major appeal of the character is both his obvious high intelligence and his sheer incomprehensibility.

The first story (and best example) I can recall where an alien with a speaking role spoke in a truly alien fashion was THE MOON ERA by Jack Williamson, where an alien called ‘Mother’ was portrayed sympathetically, albeit clearly not human. She was an alien and not a monster.

Oddly enough, the second best example comes from HEROIC AGE, a Japanese anime, where the Silver Tribe were portrayed as both elfin and highly intellectual, whose concerns were understandable, but were not human concerns.

However, the most common use of aliens who are aliens and not monsters derive from GALACTIC PATROL by E.E. Doc Smith. In that background, creatures of different psychology and different morality from man—such as the plutonian Palanians who are as cowardly as Nivens’ Puppeteers, or the placid Rigelians who are morally perfect but too placid and inert to commit heroic acts, or the berserk and bipolar Velantians—all are faced with a common threat, and all are loyal to the ideas of reason and the ideals of civilization and democracy.

Everything from STAR TREK to the composition of your average party of adventurers in a Dungeons and Dragons game reflects this “melting pot” idea of the Galactic Patrol. I cannot bring to mind an example where the underlying tale is not a war story, an expedition or adventure involving physical danger, because that is the kind of thing where team spirit is both necessary and expected.

In such stories, if the story is done right, the elements or quirks that make each race different from the others is present, but is overcome by their common camaraderie, their team spirit. When it is badly done, the aliens are just humans in stage makeup, and all their differences are on the surface, so there is nothing for the team spirit to overcome.

I should mention that many of the most famous science fiction authors have some of the least convincing aliens. This may be due to the editorial influence of John W Campbell Jr, who did not like stories where aliens were superior to humans in any way.

But, for example, in Robert Heinlein’s HAVE SPACE SUIT WILL TRAVEL, the Wormfaces are just monsters. There is no pity spared for any of them, none have names, none express any regret or differences of opinion about their role as world conquerors and eaters of man. And the Mother Thing, one of Heinlein’s best aliens, is suspiciously similar to the Mother from Williamson’s THE MOON ERA, which I mentioned above. The Mother Thing has one personality trait: she is loving. Heinlein does a better job with his Martians from STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, by making them, in their adult stage, sexless, and therefore, according to Heinlein’s theory of psychology, utterly lacking in drive and ambition.

Again, the aliens in Arthur C Clarke, such as his Overlords in CHILDHOOD’S END or his monolith-builders in 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY, are not really alien as much as transcendent and incomprehensible: Tweel with godlike powers.

The prize for the best aliens, in my judgment, should go to Poul Anderson. I hope I will be forgiven if I praise this lesser known author too much, but he actually took the time to invent plausible social and psychological differences between his invented creatures and mankind and base them on plausible differences of biology, sexual strategy, diet and evolution.

I will point out that fantasy and fairytale rarely if ever portrays the nonhuman intelligences, talking dragons or singing elves, encountered in the tale as unlike man, except that the supernatural or infernal creatures are greater in age or dignity or power.

Elves usually have kings and queens as we do, and rarely — Tolkien is the great exception — do they have histories and kingdoms and wars. In this regard, Tolkien’s elves are almost indistinguishable from Man. They seem to be long lived men, the main difference being that they are not under the curse of Adam, in that they do not seem to plough fields and grow crops and send out fisher-folk for food. If they hunt, it is for sport. The point of Tolkienian elves is that they are unlike Shakespearean elves in MIDSUMMER’S NIGHT DREAM, who were diminutive tricksters and sly spirits. But note again both the elves of Tolkien and Shakespeare are closer to nature than Man, or are at one with nature, or are its guardians and tenders.

Now, some say the elves and dwarves of myth and legend are the lesser spirits or fallen gods toppled from Olympus by the triumph of the God of Abraham, and the growth past polytheism into a more sophisticated worldview, that is, there are a memory of the Old Gods which echoes in the nursery tale. I have my doubts: such explanations strike me as “just so” stories invented after the fact to explain stories without explaining them: giving the efficient cause rather than the formal cause. I am more inclined to believe the simpler story that elves are spirits of the woods, like dryads, and mermaids are sirens and sea fairies, and dwarves are earth spirits or svartalfar, personification of the powers and beauties and terrors of nature, or memories of angelic powers, fallen or unfallen, our ancestors dimly sensed moving behind the stage scenery of the world.

You see, no one by definition can desire a communion or community with a beast, or a tree, or a mountain, a sunset or a storm or a sea wide beyond awe’s own power to measure. What we all yearn for, those of us who are not unfit in our hearts, is communion and speech with the intelligence behind these things, the spirit of nature, or, if you will permit me, the author of nature. Those with fit hearts can tell instinctively from the beauty and order of nature that a great and potent Creator made all these wonders.

If Mother Nature were the blind machine the moderns blaspheme her to be, none of her products would make us catch our breath in fearful admiration, neither nebulae nor novae nor rearing stallions nor rushing rivers nor gentle rains nor the smile of the rainbow. If there is no Designer, there is no grand design to admire, except perhaps for that which the pattern-seeking frailty of the human mind, staring at a Rorschach inkblot, decides to deceive us into imagining we see.

At this point, we can answer the two parts of the question that was asked at the beginning.

Snow White can cajole the beasts of the wild to aid her housekeeping because she is an image of sweetness and innocence; and one of the most powerful images of innocence, the innocence of Eden, is the image of Nature herself blessing and loving and aiding the unfallen innocent. A clear and charming symbol of this blessing is the aid of natural animals bestowing their friendship, and a clear and charming symbol of the supernatural nature of the aid is to have the animals cross the gap severing the sad children of man from Eden, to act, for an afternoon, for a brief and magical hour of music, as man’s true friends, able to aid us in our work.

We are all exiles here. Christians believe this literally, but nearly all of mankind no matter of what belief feels at times the same way.

(Perhaps John Galt from Ayn Rand’s ATLAS SHRUGGED is an exception: but then again, by his own bold estimation, he is a prelapsarian man, since he boasts of being untouched by original sin.)

We yearn for the blessing of Nature and communion with her, and this yearning, for reasons only Christians can explain, is a nostalgic one.

As I say, to tell stories about unfallen virgins in fairy tales or savage princes able to tame bears and wrestle lions, which is fairy tale; and to tell stories about the talking animals of other planets, which is science fiction; or the talking animals of earth, or elfin spirits of wood and mountain, which is fantasy — all such tales are like looking at a picture of an absent loved one.

And, despite what other science fiction authors will tell you, the evidence for life on other planets is and continues to be zip, zilch, nada, nothing, and the evidence for intelligent life is even less, and even if they were there, no electronic signal of ours will ever reach them nor any of their signals reach us—space is just too big and life is just too short and the speed of light is just too slow. From a purely scientific point of view, there is more evidence of Elves than there is evidence of Martians. We have at least some eyewitness reports of elves seen by people in Iceland.

So why is intelligent aliens one of the most common ideas in science fiction?

Why do we tell imaginative tales like this? A detective story, even an unlikely one, could be true, and could happen, as could a story about cowboys or pirates or knights or braves or samurai, and love stories could happen and do. But no muskrat is ever going to clean your sink, and I sincerely doubt a boy raised by wolves is going to defeat a tiger in combat. And you will never talk to a Martian.

Why? The first reason I already said. We are lonely for the nonhuman intelligences which science fiction fans speculate may be in the heavens, and which Christians firmly believe compose the stellar hosts of heaven.

The second is a far more powerful reason. If Man were merely an intelligent animal, something derived by blind natural selection, and bred only for our ability to continue breeding, then we would not tell stories. It is a useless habit, that neither secures food nor wards off predators nor aids in the seduction and rape of she-humans, nor increases the number of her spawn.

Some might say that it is a side effect of language using ability, a defect of the brain, so that we humans misuse that faculty of imagination nature evolved in us solely for planning military campaigns against rival tribes of mastodon hunters, and the linguistic skills to coordinate hunting and fishing and slaying rivals. Some might say language was evolved to be precise and scientific, merely a tool for remembering facts of the past we have seen and constructing speculations of the future we shall see, and that this tool of language is misused if we play make believe about things not of the past or future, and attempting to peer into the unseen realm. I say those who say story telling is an abuse of the faculty of language are abusing their own faculty of language, and telling us a story, and bad one.

I propose we want to give tongues to animals and woods and waves and we want to command the mountains and the clouds to speak to us because we yearn to be creators ourselves. What greater gift can any father give his child than to teach him the gift of speech? If we had the power to grant this gift to our pets and livestock, surely we would, and indeed, to exchange defiance and threats and terrifying boasts with the lions and wolves who are the enemies of man would also be a delight. Beyond this, to speak to the river and ask it why it runs, or to the sunshine and inquire of its cheer, or to command the raging storm be silent, this is a delight that saints and angels know which man, exiled from Eden, has lost. We are dumb and deaf in a world given to our dominion.

I propose that there is something of the creator in the poet, and that this is because we are created by a Creator in His own likeness and image, and so naturally must reflect the nature of creation in us. We want to bring things to life, to create worlds, to grant speech to animals and to command nature, because that is the joy of creation.

We cannot, in this life, create world, except in fiction. We cannot possibly have this desire from anything in nature. It is supernatural in origin.

It is like a young man in love daydreaming about the words and sighs and kissed he means to exchange with his beloved. The daydream raptures him, and draws his thoughts away from the dirt and toil of his daily life, and for an hour, in his heart, he dwell in the bliss of the honeymoon cottage. But there is an element of sorrow and longing and sadness in his daydream, or in him, because it is not real. It does not truly satisfy him.

Let me end, as befits a writer of speculative fiction, with a final speculation. Should we ever find a world like Perelandra, whose happy natives resisted the temptations that toppled the Adam and Eve of Earth, or should we ever reach in a next life the cosmic realms inhabited by archangels and dominions and potentates and powers, it is possible that they might not tell stories of the imaginative kind discussed here. Psalms and hymns, to be sure, or epics of praise for glorious deeds, or love songs, or all the other kinds of tales the other muses inspire, all might be present in the unfallen world.

But stories of fairytale and fantasy and science fiction I speculate may indeed be absent in those happier and higher realms. The saints in heaven will have realized the immense longing we here in exile on Earth cannot fulfill on Earth. They will do as their Father does and sings the songs of creation.

Imagine instead of imagining the talking cats of Kzin or dragons of Pern, using the gift of speech as we all secretly know it is meant to be used, and speaking the worlds and stars into being.

Why should they daydream, and not do? No youth sighs over his beloved’s picture when she is in the bridal bower and demurely shedding her veil.