Review: THE BLACK CAULDRON by Disney

Rewatching the feature length Disney animated films in chronological order gives one a sense of the changes wrought by the changing years.

With THE BLACK CAULDRON (1985) we are still in the Dry Spell of lower quality films suffering from the lack of Walt Disney’s own genius, but we are nearing the end; for perhaps some hints of the Disney Renaissance to come are in the offing.

As with any Disney film, for some, this will be a favorite of treasured memory lodged in the heart, because it was encountered during the golden years of childhood. Alas, I am not in their number, having seen it during my grad school years.

Others regard this film with a jaundiced eye, calling it the worst fumble of Disney to date. I am not willing to be so harsh, merely because the technical accomplishments of the film are striking.

For example, the scene where evil birds chase a terrified pig across a moving landscape in dramatic swoops of the camera is my only clear and bright memory from when first I saw this film as a young man. Even upon rewatching, the technical brilliance is equal to scenes from Miyazaki’s CASTLE IN THE SKY.

But I must confess at the outset that I cannot be objective about this film. I was and am a deeply devout fan of Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain books, which shaped my childhood imagination. Every deviation from the source material irks and chokes and offends me.

Some are minor albeit pointless changes: Hen Wen, the oracular pig, is pink rather than white, and Eilonwy of the red-gold hair was changed to a blond. Some are major changes which ruin the story, as who is thrown into the Black Cauldron at the end, the nature of Dyrwyn the magic sword, the death of the Horned King.

The sharp contrast between the genius of the books and the folly of the film seems well-nigh blasphemous.

I will make an ambitious attempt to maintain fairmindedness, but, I fear that, like the film itself, this review will be an ambitious failure.

THE BLACK CAULRDON bombed in the box office, and critics of the time could not help but compare it unfavorably to SECRET OF NIMH, released not long before, the masterpiece of Don Bluth, who departed from Disney in a fit of pique, taking a dozen talented animators with him. Another film released not long before was STAR WARS by George Lucas, and the attempt to mimic camera motion elements or the lightshow special effects, particularly in the case of the magic sword, is obvious.

Many fans consider BLACK CAULDRON Disney’s greatest failure, a failure made more ironic by the ambition of the attempt.

There is no question but that it is a failure, with weak writing, poor pacing, bad worldbuilding, pointless plot lapses, extraneous yet forgettable characters, irksome sidekicks, gratuitous horror, and an unsatisfying ending.

But let us be fair: the draftsmanship, the backgrounds, the special effects, the striking visuals remind one of Don Bluth at his best. The spooky castle of the Horned King could have been taken directly out of the video game DRAGON’S LAIR.

The film was reaching for a teen boy audience, less family friendly, and so included grisly scenes of skeleton warriors and death by disintegration that shocked the test audience of younger kids. This led to awkward cuts made in haste which the sharp-eyed can spot. This is the first Disney animated film to get a PG rating, and also the first with no musical interlude, no songs sung.

The story is loosely based on elements taken from the first two books of Lloyd Alexander’s immortal Prydain series, THE BOOK OF THREE, and THE BLACK CAULDRON.

The film beings with a voiceover (by the legendary John Huston) explaining the grisly origin of the Black Cauldron, which can raise a zombie army able to conquer the world.

We then cut to Dallben the Enchanter, a remarkably unremarkable wise man, muttering and fretting to himself about the threat from the Horned King. We meet his serving boy Taran, assistant pig keeper, who daydreams of being a great warrior, harassing a flock of geese with a stick in pretend battle. This young swineherd has but one swine: the piglet Hen Wen, who is able to conjure visions of far places in her waterbowl.

Dallben conjures a vision of the Horned King, and learns that the villain seeks to capture Hen Wen to use her oracular powers to discover the hiding place of the Black Cauldron.

It is not clear whether the act of using the oracular pig is what brings her to the Horned King’s attention, in which case Dallben was foolish to use her, or whether the Horned King knew all along, in which case Dallben was foolish to wait before using her.

Dallben then orders Taran to take the pig to some place of safety, but she escapes him while he is daydreaming, and is captured by the evil bird monsters, Gwythaints, in service to the Horned King.

Taran meanwhile is mugged by the small and cowardly half-monkey, half-Pekinese named Gurgi, who speaks in a comical high-pitched helium-voice. Taran scorns and menaces the annoying creature, who immediately declares him to be his friend and master, vowing comically to find the missing piggy.

I must mention that Gurgi in the book is described as tall and big enough to wrestle Taran, a half-man half-animal whose sharp eyes and woodlore aid the hero many a time.

The film kept the self-rhyming speech pattern and third-person speeches, but a Gurgi who is the size of an ape, able to ride a horse or wield a weapon, is funny and sad when he fawns over the great and mighty, and worries his poor, soft head might be struck. When a critter the size of a small puppy does the same, the humor is oddly bent. Unlike an ape, a puppy struck with a strong hand might severely wounded. Gurgi from the books is one of my most favorite characters of my youthful reading; Gurgi from the Disney is one of my least favorite of any Disney character.

Gurgi leads Taran to the ruined and haunted castle of the Horned King, but is too frightened to enter. Taran scoffs at his cowardice, enters, trips and falls, and is immediately captured. Not to worry, Taran will escape when the guards all trip and fall all over themselves likewise. Stay tuned.

The Horned King himself is an impressive and spectral figure, looming on his dark throne surrounded by mists, and memorably voiced by John Hurt, speaking at times in a slithering whisper, at times in roaring rage.

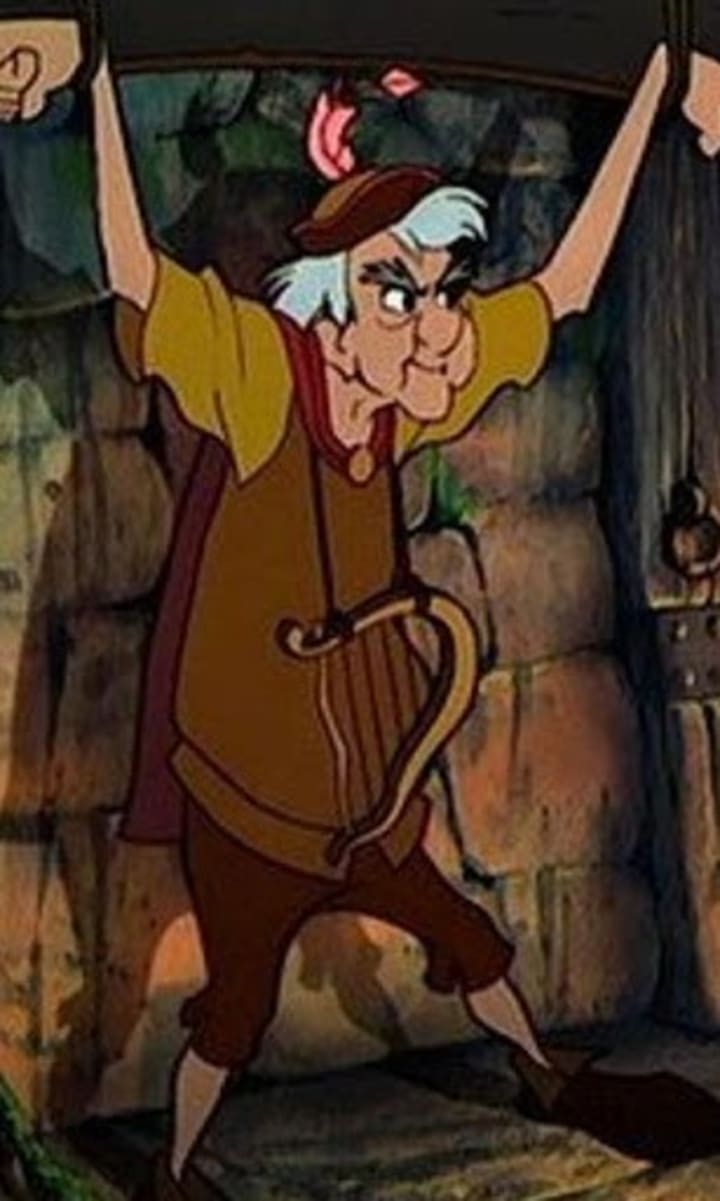

The Horned King’s comedy relief flunky, a sniveling goblin named Creeper, does most of the talking, and is annoying and pointless beyond words: as if Sauron kept Three Stooges as Ringwraiths to do slapstick pratfalls, but not as funny as Mo Howard.

Likewise, the henchman guards of the Horned King are rowdy unshaven louts with beer bellies, some in Viking helmets, seen feasting, dicing, in the midst of the cobwebbed and rotting ruins of the hall. The serving wench flirting with them is an unsightly and overweight big-bosomed hoyden, whose character design we will see again as one of the three witches at the climax of the film.

These henchmen neither evince the menace of barbarians, nor the discipline of stormtroopers. As if Darth Vader kept a biker gang as retainers. The troops shown are not numerous enough to form a threat to any neighboring kingdoms, which is ameliorated, I suppose, by the fact that no neighboring kingdoms are ever seen on stage. The Horned King is a menace never seen menacing anyone aside from our three main characters.

Compare and contrast this with similar scenes in MULAN, where the Mongols leave behind burned villages strewn with corpses. The world there includes more than the three main characters. Contrariwise, no neighboring kingdoms are seen nor mentioned in SNOW WHITE or SLEEPING BEAUTY, but then again, the evil witch or bad fairy there is trying to kill a single girl, not conquer the world.

The comedy of Creeper does not mix well with the horror of the Horned King, and the fumbling brutality of his biker Vikings is at odds with the eerie supernatural appearance of their boss.

In sum, the toady, henchmen, castle, and goals, and nearly everything about the Horned King is tonally awkward, an admixture of elements that never combine into anything memorable or sensible.

But to return to our plot: The Horned King then threatens to butcher the pig unless Taran uses Dallben’s magic words to conjure the vision of the hiding place of the Black Cauldron. Deciding the pig’s life means more than world conquest by the undead, for the pig is quite cute, Taran agrees.

But before the hiding place of the Cauldron is revealed, for no reason I can recall, the pig’s waterbowl is splashed in the face of the Horned King, who cries out for no reason in pain as if scalded by acid, the evil birds for no reason break free of their chains, and guards rush in, stumble over the evil birds who stumble over them.

And every bad guy gets in every other bad guy’s way. Taran hotfoots it out of there with the pig wiggling under his arm, reaches a crumbling balcony and tosses the pig down the zillion foot drop into the wet rocks of the shallow moat. Taran is immediately recaptured by a small creature the size of racoon, and no one sends a guard outside to fish the pig out of the moat. Hen Wen makes a clean getaway, proving she is a magical pig after all.

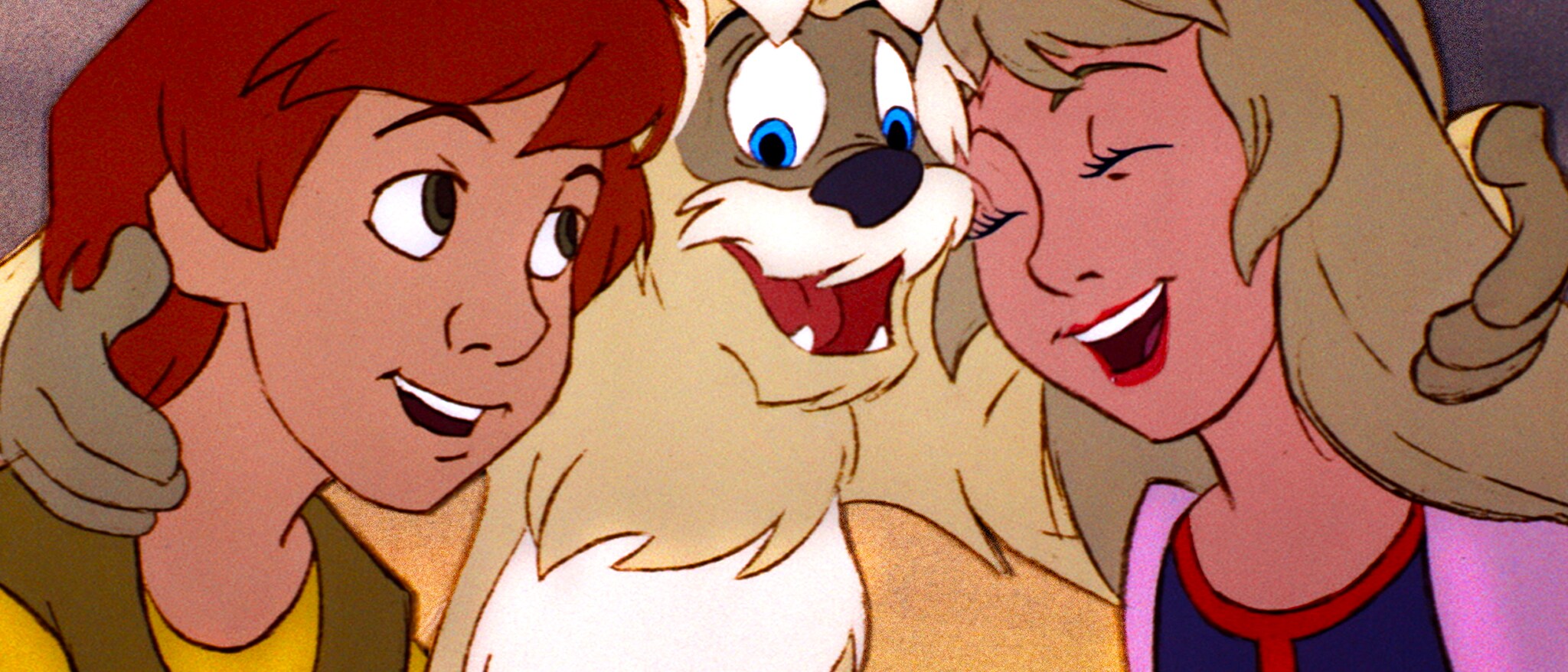

Taran is in chains in his dungeon cell when Eilonwy, the spunky princess, enters his cell via trap door, a glowing bauble floating beside her. This bauble is one of the more striking visual elements in the story, gleaming and soaring as if with a mind of its own, changing colors subtly as if pleased or angered, or when chasing rats.

Unfortunately, the real background from the storybook never comes on stage here, nor is the secret that the book-version of Taran discovers about the orb when he is trapped in the dark without Eilonwy. That she is an enchantress in training is likewise never mentioned, nor her background, nor is there any explanation of how she freed herself from captivity.

It is however mentioned in passing that the Horned King kidnapped her in hopes her magic bauble could help him find the Black Cauldron, which almost makes sense, as long as one does not think too hard about it.

The hidden power of the magic bauble in the books, which allows one to read hidden charm-runes written in invisible ink, is here nowise mentioned. Fans of my own writing my be alert enough to recall where I shoplifted this idea for my own use. Disney makes no use of it, nor is there a scene where she illumes an entire dark landscape in an hour of need.

If she is meant to be the love interest, the scenes of comedically awkward puppy love between the teen protagonists are awkward and flat, and have been done better in every Disney movie, including ROBIN HOOD and ARISTOCATS, whose romances were clumsy, unmemorable, and handled half-heartedly indeed.

The contrast with the book version of Eilonwy sets my teeth on edge, and I cannot write calmly, lest I smash my keyboard in frustration. I will say only that Eilonwy has the most vivid personality, the most spunk and charm, and the best lines of any female character I read in the countless books of my bookish youth, bar none.

Hardly a day goes by in my household were someone, adult or child, fails to quote her immortal wisdom:

“It’s silly,” Eilonwy added, “to worry because you can’t do something you simply can’t do. That’s worse than trying to make yourself taller by standing on your head.”

In the film, after helping Taran escape, Eilonwy thereafter does nothing of note, not even get menaced to serve as a damsel in distress, which, at least, is an honorable pastime for any fairytale princess. On the other hand, in a final scene, Eilonwy lifts Taran’s drooping spirits by inspiring him with a grossly uninspiring slogan, telling him to believe in himself.

Since she actually makes real but rare inspiring speeches in the original books, this adds insult to injury.

“Prince Gwydion’s the greatest warrior in Prydain,” Eilonwy replied. “You can’t expect everyone to be like him. And it seems to me that if an Assistant Pig-Keeper does the best he can, and a prince does the best he can, there’s no difference between them.”

A trifle of her spunk is perhaps seen at her introduction in the film, when she appears as a Princess Ex Machina to spirit Taran out of durance vile, but even that element makes no sense.

In the real version, the book version, Eilonwy by mischance finds Taran captured in the Spiral Castle where she is staying, allegedly the niece of the evil crone tutoring her, and after an amusing conversation ripe with misunderstanding, she decides to help him escape.

In the film, she is the calmest and most unhurried escapee of all time, with no one pursuing her, no alarms ringing, and no clue spoken as to how she escaped her cell and found a convenient endless maze of secret passages.

During the escape through the miles of conveniently unoccupied basements and dungeons, the pair encounters the crypt of a dead king Eilonwy identifies as the original owner of the castle. From the open sepulcher, Taran filches the sword with which the king was buried, and discovers it to be a magic sword when guards stumble upon them.

Unlike in the original, no name nor backstory is given for the blade, and no one need be found worthy before drawing it. Eilonwy’s role as the keeper of the sword is likewise lost. In the book, she recognizes it from her Enchantress lessons, it is found in the Spiral Castle where she lives, and she keeps it from the eager hands of Taran. The crucial fact that at first he cannot use it is likewise lost to the tragedy of trying to cram several epic volumes of source material into a single self-contained standalone movie.

In this film, the blade burns and shatters any weapon it touches, and the biker Vikings are in too much awe of it to overthrow the untrained and outnumbered Taran in a rush. He can cut threw stone columns and collapse walls on pursuit.

Shortly thereafter the unexplained secret passages lead the pair into the cell of Fflewddur Fflam, boastful bard.

Of Fflewddur Fflam, there is not much to say. His background as warrior and petty king, his fear of magic, and the origin of his harp is never mentioned.

The character design for Fflewddur Fflam is remarkably similar to the look and hesitant speech-mannerisms of Dallben, so much so that I had to pause and rewind the film to confirm they were not the same character or same voice actor.

But Dallben is the most visually unremarkable wizard or conjuror Disney ever conjured, even as Eilonwy is the least princesslike princess in her costume, the least magical enchantress. No one in this film has anything in costume or look that appeals to the eye or remains in the memory.

Lloyd Alexander provided a description of the truthful harp for the illustrator in a letter from 1966, writing that the harp must “follow the design of the ancient Irish harp, which has a truly gorgeous harmonic curve and curved pillar (not the ancient Welsh harp, which has a straight and homely looking pillar).” In film the harp is precisely this homely looking design, unadorned and undersized, hanging comically at the belly button of Fflewddur, where it would simply bounce against his belt buckle as he walked.

The amusing conceit in the book is that his harp is charmed to break a string every time Fflewddur Fflam strays from the truth into the windy boasting to which he is prone. Here the bit is kept, but nothing much is made of it.

Unlike in the book, he plays it only briefly, or not at all. I do not remember. There is nothing akin to the remarkably touching scene in the book where he sacrifices the precious harp to save his friends, a scene which has few parallels in any fairytale.

Like Eilonwy, Fflewddur Fflam is thrust into the tale because he was in source material, and like Eilonwy, this most memorable and beloved of characters is turned into a forgettable stock character, and given no role to play in the plot. Like Gurgi, he is portrayed as comically craven and cowardly, but unlike Gurgi, he has no moment of startling redemption.

Fflewddur Fflam has no reason to remain with the children once they escape the haunted castle of the Horned King. Nonetheless, he does.

The Horned King unexpectedly sends no pursuit to recapture the fleeing trio, but instead dispatches his monster birds to follow them, in hopes of being led to the lost pig.

The trio fall in with Gurgi again, who again tracks the pig by her spoor, this time to the edge of a magical pool, which abruptly swallows all four of them.

They are whisked, not in the eerie Celtic underworld, but into a cave of flickering fairies drawn in a dumpy and comically round-faced style utterly unlike what is seen, for example, in the Nutcracker sequence in Disney’s FANTASIA. The fairies look and talk like toddlers.

The fairies kidnapped Hen Wen and keep her washed and well fed. Why they did this, or do anything, is unclear in the film, albeit perfectly clear and sensible in the book.

The fairy king is one more chubby and muttering oldster drawn from the same template as Dallben and Fflewddur Fflam. By mistake he lets slip the location of the Black Cauldron’s hiding place: the haunted hut of the Three Witches in the Marshes of Morva.

Taran immediately vows to find and destroy the cauldron, rather than letting it rest in the hands of the Three Witches, where it is utterly hidden and utterly safe. The fairy king offers to return Hen Wen to Dallben’s undefended cottage, rather than letting her rest here in the underground fairy world where she is utterly hidden and utterly safe.

The fairy king moreover sends the comically overworked and comically incompetent yet sharp-tongued fairy gaffer Doli with them as a guide.

The real Doli from the books is charming, memorable, and amusing, and turning invisible makes his ear buzz. That bit of characterization is dropped. And like the other characters here, he is thrust into the remaining scenes with little to say and nothing to do.

Arriving with no more ado at the haunted cottage of the Three Witches, the group searches an empty cobwebby hut and is pointlessly attacked by a host of flying pots and pans, which the magic sword cleaves in twain.

The Three Witches put in an appearance. Their true meaning as told in the books is absent from the film, of course.

Two of them are modeled after the unpleasant villainess from THE RESCUERS, comedically angular and cackling crones, while the third once, a comedically overweight and buxom man-hungry flirt with an immense cleavage, immediately decides to chase Fflewddur Fflam about the hut, lusting for his kisses, and changing him back each time her sisters change him into a frog.

In one of the more confusing bits of magical business in the story, the witches offer to trade the Black Cauldon for the magic sword, which one of the witches craves for no clear reason.

Let me pause to remark that the main thing making a fairytale a fairytale and not some other form of related story-telling is that any magic seen in the tale must be both arbitrary and ironclad. If only true love’s first kiss breaks the curse, the kiss of an inconsistent lover will not do. If the princess must leave the ball by midnight before her magic dress and equipage fades, she cannot argue for an extension. Three wishes does not mean four.

Likewise here: if the Black Cauldron is to be traded for the heart’s dearest hope, it cannot be swapped back later on for some other reason. The bargains in myths with supernal beings are binding and strict: the sacrifice is real and the price must be paid. Without this, there is no drama, and the stern rules of the Perilous Wood, where fairies dwell, evaporate into mere daydream-stuff.

At first, it seems as if Disney is able to grasp this point, and carry it onto the screen from the books.

In one of the two scenes that is actually noble and touching, Taran agrees to surrender the sword, thus dashing forever his hopes of being a great warrior.

The exchange is made, the Cauldron released from its hiding place, and the cackling witches reveal that the Cauldron is indestructible unless a willing victim leaps into the mouth of his own free will and dies. Away they fly in a whirlwind.

The trio do not ask Doli to take the thing and hide it in the fairy underworld, nor do they draw straws to see who must leap in and destroy it to save the world. Instead they sit glumly, doing nothing.

Then the monster birds swoop down and carry it off.

Gurgi flees and the others are captured post haste by biker Vikings, and are immediately spirited back to the Dark Tower and strung up by the wrists to witness the ritual as the Horned King raises his zombie army.

A horrific display of excellent draftsmanship follows in one of the many well drawn scenes in this well drawn movie. The zombie army of skeletons rises from the castle mass grave, and stumbles into eerie motion.

The Viking bikers all flee in panic, and the small squad of less than a hundred corpses march out across the drawbridge, apparently a menace able to conquer and the whole world.

The Horned King also departs for the balcony to view the scene, leaving the Black Cauldron, still bubbling and spewing evil mists, still powering the small but unimpressive zombie squad, utterly unattended.

Gurgi then sneaks in through a crack in the wall, and comes to the rescue, unties our heroes. When Taran climbs on a narrow ledge above the cauldron, preparing to sacrifice himself and end the threat to the world — for all the zombies will perish once the cauldron is destroyed — Gurgi steps in the way. He explains in his sad, childish voice that Taran cannot kill himself, because Taran has many friends, whereas Gurgi has no friends.

It is the second of the two scenes that is actually noble and touching.

Gurgi dies.

It is a dramatically moving scene, dramatically undermined a few moments later when he springs back to life and continues snuffling and sniffing for crunching and munchings. More on that below.

A whirlwind of evil energy emerges from the cauldron when Guirgi swandives to his doom in the evil cauldron mouth, and the zombies collapse.

Taran inexplicably crawls toward the cauldron, inexplicably saying that Gurgi might still be alive.

The Horned King, rather than standing by and watching Taran get destroyed by the whirlwind, inexplicably steps into the whirlwind himself in order inexplicably to menace Taran, but he is pulled into the mouth of the cauldron, where he is slowly and painfully torn to bits as he disintegrates in what is surely the most grotesque death-scene Disney ever produced.

How and why the Horned King is slain merely by standing near the Black Cauldron during its destruction is not explained. Tossing in an unwilling victim was not said to do anything in particular, but maybe the rules change once the Cauldron is in its death throes. But the scene is remarkably well animated.

The corpses flop over, the Viking run away, the runty sidekick mourns his dead master momentarily but then starts giggling about it, and flies off on the back of the last monster bird to live happily ever after.

The Three Witches appear in a cloud of maleficis ex machina and offer to take the now-broken cauldron back. Why they want it back, now that it is broken, could have been explained in a word, but is not.

Now Fflewddur Fflam, in his one moment of usefulness, challenges the Three Witches to bargain for what they want, throwing their own words back in their faces.

The Witches attempt a trade. Taran is inexplicably offered his sword once more, and, inexplicably, once more refuses. Two scenes ago, the Witches wanted the sword more than the Cauldron when the Cauldron was magic. Now that it is scrap iron, they want it more than they want the sword. Taran has no possible need for a broken cauldron, and every reason to recover the all-powerful sword.

Taran asks for Gurgi to be resurrected, which the Three Witches say that they cannot do, but Fflewddur Fflam speaks scornfully and taunts them into doing it. The exchange makes no sense to me, but I am tired of typing the word “inexplicable.”

The witches disappear in a whirl of magical lightshows, and fly off, taking the broken and useless Cauldron with them. Gurgi’s motionless body is seen left behind. Taran cradles it for a tense yet sad moment of silence.

Gurgi springs to life, and is annoying once more. The camera pans back, and we see Dallben safe at home, watching these events unfold in the waterbowl of Hen Wen, who snorts happily.

Roll credits.

The characters are both the most bland and forgettable Disney ever produced, which is a remarkable feat considering the richness of the source material.

The theme running through the frustrated dreams and aims of Taran, of Gurgi, of Fflewddur Fflam, and even of Eilonwy, who, in the book, all have to struggle with their shortcomings to accomplishing true heroism, are absent in the film, save only for Taran’s character arc where he dreams of battle, irks geese, gains and then foreswears the magic sword.

The book is about sacrifice and hard choices, and the film attempts perhaps to copy this, but, if so, bungles badly.

To be fair, the worst errors of the Dry Spell are no longer in evidence. The villain is scary, not merely bungling comedy relief, and the slapstick is kept to a minimum, and is realistic rather than cartoonish. And who, after all, does not want to strangle Creeper?

The scenes move smoothly from one to the next, and the pace is kept, even if the events are disconnected, with no clear through line.

The worst thing about this film is the lack of any sense that there is a world behind the characters, rather than a painted backdrop. A film set in long ago and far away, as in SNOW WHITE or SLEEPING BEAUTY need not have any background, since we all already know what fairytale-land is like. The generic Northern European Middle Ages is background enough.

But this film was set in Prydain, the Isle of the Mighty, and should have looked and felt like medieval Wales. There should have been something distinctive about the dress and development of each character. I am not saying Dallben needed a pointy hat like Merlin in SWORD IN THE STONE or a magic wand like the fairy godmother in CINDERELLA, but he needed something to make him look like someone, even if one lacks the skill to make him look distinctly like a Welsh enchanter.

The bard needed to look and act like a bard. The princess who is also an enchantress in training should have looked and acted like one. Even the Horned King, as impressive as he was, fell short.

Oddly, the film would have been improved had it been less faithful to the books. The characters of Coll and Gwydion were dropped, and nothing of the original Welsh myth on which the Lloyd Alexander’s books are loosely based is preserved, except the names. So why not drop the characters of Eilonwy and Fflewddur Fflam? They do not actually have anything to do, despite that one has a magic harp, and the other has a magic bauble.

But there is no magic in this film.

Not recommended. In fact, highly not recommended.