Review ALADDIN by Disney

We continue reviewing all the Disney feature-length animations in chronological order. We are now in the years of the Disney Renaissance, when the original skill and genius of the company was revived by the Broadway musical inspiration of Howard Ashman. By this time, he had passed away, and his loss is noticeable.

ALADDIN (1992) is one of Disney’s finest accomplishments, equal to the best animation ever put to film.

The critic must use a magnifying glass to find flaws with any element of the animation, characters, plot, musical numbers, but, albeit small, those flaws can be found.

Were this film not following directly BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (1991) to audience to whom LITTLE MERMAID (1989) was still fresh in memory, the flaws would perhaps not be found.

The film is very loosely based on the story of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” from ONE THOUSAND AND ONE ARABIAN NIGHTS ENTERTAINMENT, but departs from the crucial scene where the African wizard deceives Aladdin’s wife by offering “new lamps for old.” In the Disney retelling, Aladdin is impoverished, as in the original, but is a street urchin and theif, not the honest son of a poor widow in a tailor’s shop. There is a cave of wonders, but no magic ring. The original story sets the tale “in an ancient city of China” — but no audience would recognize Aladdin as a chinaman, and no retelling of the story retains this idea.

The film is more closely based on English fantasy THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (1940), which established the Hollywood idea of Near Eastern fairytaleland. All the elements, from the evil Grand Vizier, to the dotty Sultan obsessed with clockworks and toys, the Sultan’s beautiful daughter, to the flying carpet, to the genie, appear in one form or another in this film. The Evil Grand Vizier is even named Jaffar, and he conspires to marry the princess.

As with THE THIEF OF BAGDAD, this film opens with a story teller in the bazaar telling the tale as if in flashback. Here, the tale is introduced by a fast-talking peddler attempting to sell the lamp about which the story revolves. Oddly, there is no end scene where this story-teller concludes the tale. It is a framing device with no closing frame.

The peddler is voiced by Robin Williams of MORK AND MINDY fame, who also voices the genie, and Disney allowed Williams free rein to indulge in his characteristic ad-libs stream-of-consciousness monologue and voice impersonations. Robin Williams frenetic style of freewheeling humor dominates the film. Anyone finding the anachronisms and absurdities of the Genie unfunny will not take full delight in this film.

The Evil Vizier Jafar seeks the magic lamp in the Cave of Wonders, which he dares not enter himself. We are introduced to his talking parrot Iago, voiced by the unmistakable Gilbert Gottfried. This is the role he was born to play. The interaction between the aloof Jafar and bellyaching Iago, switching between servility and camaraderie, make them perhaps the most charming villainous duo in the Disney canon.

Aladdin is introduced in a Broadway showstopper “One Jump” where he sings about stealing a loaf of bread to stay alive. His comedy relief sidekick, the monkey Abu, is actually comical, not to mention an effective sidekick, as expert a pickpocket and lockpick as his master. Unlike Iago, he never actually speaks, but almost does so by making suggestive monkey-noises.

After Aladdin escapes from the bullying guards with extraordinary slapstick effort, our young rogue comes across two big-eyed waifs picking through garbage for a morsel, and, with unexpected generosity, surrenders his stolen loaf to them. It is the perfect character introduction.

Usually thieves make for unappealing protagonists, but audiences will cheer for the underdog, will understand someone driven to crime by necessity, and will forgive a thief who steals from a bigger thief, or a bully, or a tyrant. The writers here uses all these tricks and tropes to give their rogue a heart of gold.

It is these same waifs Aladdin saves a moment later from the whip of a sneering prince on a sneering steed, whose barbed insult cuts Aladdin more deeply than any whip.

Some of the rhymes in the “One Jump” song are clumsy, lacking the perfect wit of Ashman, but it is nonetheless a lively and serviceable song, eminently hummable, which, in a haunting reprise, also displays the character and motive of our protagonist.

One clever trope of a well done musical to put his deepest desire in the lyrics of his first song, telling the audience what he wants in life. The irony here is double, because the lyrics say he wants the world to look closer and see him as he is, but he spends the second act of the film in disguise.

Jasmin, the beautiful Sultan’s daughter, is dissatisfied with her fate, as the law requires she marry a prince, but she, of course, would prefer to marry for love. After quarreling with her father, she escapes over the walls of the harem, finds herself in the marketplace, from whose dangers Aladdin must use his street smarts to rescue her.

Love blooms, and the film is careful to show why these two, who should have nothing in common, actually have much in common. It is done clever in a single line they both recite at the same time, surprised to realize that the other feels the same way.

Disney has drawn many a fair and beautiful princess for many a film, but Jasmin must be ranked as among the most attractive, if only for her generous clouds of raven hair and lustrous eyes. Indeed, the animators here took extra care to make every harem girl as alluring as possible, much as was done with the blonde village girls from the last film, an eye pleasing design modern Disney lost the will to copy.

In due time, Jafar by magic discovers Aladdin is destined to enter the Cave of Wonders. Jafar abuses his authority as Vizier, without knowledge of the pump and dimwitted Sultan, to have the boy arrested, but then to arrange his escape. Jafar leads Aladdin is led to the Cave of Wonders, which is drawn with remarkable splendor and wonder equal to its name. Gold, gems, and looming statues fill the vastness.

Here we meet the Flying Carpet, one of Disney’s cleverest characters, who manages to portray a vivid personality, despite lacking a face or voice, or any means of expression aside from rug-pantomime.

Betrayed by Jafar, trapped in the cave and left to die, Aladdin rubs the lamp and releases the genie, who sings the second showstopper of the film: “Never Had a Friend Like Me.” This song has no clumsy lyrics, but is a wild display of verbal cunning, if not craziness, well in keeping with the William’s portrayal of the genie.

Unlike the cruel and mocking genie from THIEF OF BAGDAD, this genie is chubby, genial and loveable. Disney here introduces a theme not seen in any prior version of the tale: the genie is the slave of the lamp, and cannot be freed unless his master wishes him free.

Aladdin’s first wish is to marry the princess, which, not being a prince, he cannot legally do: so the genie conjures up fine clothing, an elephant, suitors and retainers, and another showstopper set piece.

However Jasmine, thinking the boy from the marketplace was executed by Jafar, and being weary of suitors craving the wealth and position her hand might bestow, scorns the fake prince.

Aladdin, warned to tell her the truth, attempts to prolong the deception, takes her on a magic carpet ride to escape the trap of palace life, which, earlier, he learned was her heart’s desire.

Another brilliant and beautiful song unfolds, marred, alas by several awkward rhymes. Jasmin penetrates his disguise, but Aladdin redoubles his deception, and is stung with guilt: he realizes he is nothing without the genie, and so refuses to free him.

Upon their return, the lovers part with a kiss. Jafar attempt to kill him, but Aladdin escapes, confronts the villain, reveals his evil to the bewildered sultan, and forces the sorcerer to flee — but now Jafar knows Aladdin’s identity, and arranges to steal the lamp from him. The genie becomes Jafar’s slave. Armed with absolute power, Jafar reduces the sultan and the princess to humiliating servitude, and banishes Aladdin to certain death in the artic.

Aladdin is saved and returned by the Flying Carpet, and outwits the invincible Jafar using perhaps the cleverest plot twist of any Disney film:

Aladdin, as we just saw throughout the film, suffers from a desire not to be despised by the world as a street-rat, to be something better. Too late, he realizes he must prove his worth himself, not to have magic hand it to him. Seeing this same weakness in Jafar, he challenges Jafar that he is nothing without the genie — the selfsame thing Aladdin realized about himself in the prior scene.

Jafar is defeated and banished and Iago is yanked off with him. Aladdin is urged by the genie to wish himself a prince again, to allow him to wed the princess, but, wiser now, Aladdin frees the genie. In a rather awkward denouement, the sultan overrules the law, and lets the two be engaged nonetheless. The genie winks at the camera and flies off, shouting and yodeling.

These characters are among the best drawn, both in draftsmanship and in detail of writing, of the Disney canon. Aladdin has a more three dimensional personality than Prince Charming, Prince Philip, or the several male leads from other Disney films, and his motives are as sympathetic as are those of the princess Jasmine. The voice acting is top notch. The genie’s personality is Robin Williams’ lunacy, but the added trope of a slave yearning for freedom gives even this nonhuman being a human side. I have already mentioned the charm of the voiceless portrayals by the monkey and the carpet, not to mention the quirky interplay between Jafar and Iago.

Only the Sultan is something of a cliché, brought unchanged from his prior stereotype in THIEF OF BAGDAD: one more ineffectual father figure with no mother, as is seen in many Disney films.

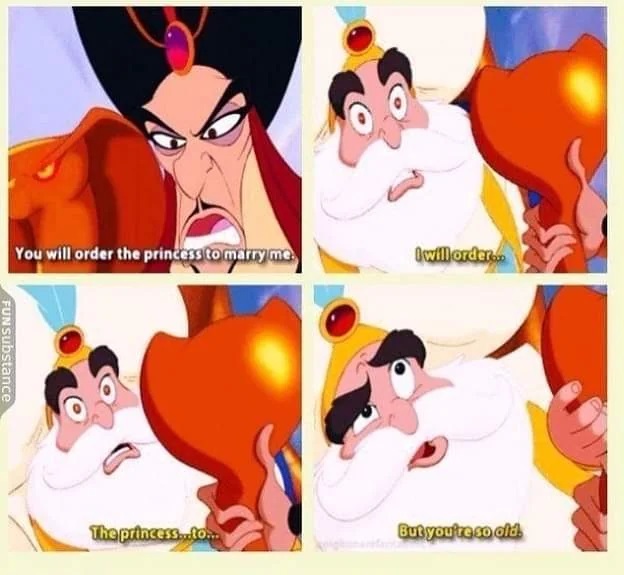

Regardless, the voice acting and the animation make the Sultan charming and funny — one cannot help but smile when, as Jafar is hypnotizing him with a magic wand, to force a marriage with the princess, the chubby little sultan looks up and says querulously, “But you’re so old!”

There is no obtrusive computer work as seen in the ballroom scene in BEAUTY AND THE BEAST. The carpet is seamlessly woven, if I may use that word, into the hand drawn animation.

The setting is in a Bagdad-style city called Agrabah, adorned with onion domes and minarets of storybook Arabic architecture, and, again, displayed with exceptional draftsmanship.

The theme here is remarkably subtle and trenchant for a children’s film, and yet clear enough for even a child to see: having one’s wishes granted means nothing if one wishes wrongly, as Aladdin does at first and Jafar does in the last.

Jafar wishes for his own power and prestige, and falls into slavery. Aladdin wishes for the freedom of his friend, humbly accepting the poverty of his born lot he sought to escape the whole film, heartbreaking loneliness of being unable to wed his true love, only to be rewarded with all he surrendered and more.

Selfish wishes end in slavery. Selfless wishes grant more than was asked.

I mentioned small flaws, but let me emphasize these would be invisible in a film not following in the august company of Disney’s best. Robin William’s genie may be too over-the-top for some audiences, and his continual stream of anachronisms might jar one out of the setting. Tastes differ.

The lyrics not written by Ashman cannot match his genius. They are not bad, but they are not brilliant either.

Aladdin’s come-uppance in the third act may seem a little rushed. He does try to make amends, but is interrupted, and then overwhelmed by events.

The major obstacle forcing the plot, namely, that the princess must marry a prince, is merely waved away at the end, when it could have been handled more neatly. (The Sultan could have appointed Aladdin vizier, for example, or granted him a province to be a principality of his own.)

One unduly irksome flaw, because it was gratuitous, was not in the film itself, or not at first, but I mention it last, because it is a flaw that lingers with me unduly.

Political correctness struck against the opening song when the work was released on home video, back when home video was new. The lyric of the opening song, whose theme is to warn of the dangers surrounding the romantic desert life of the Arabian Night’s Tale about to begin, reads:

” Oh, I come from a land, from a faraway place,

where the caravan camels roam.

Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face;

it’s barbaric, but, hey! It’s home.”

Casey Kassem the disc jockey famed for nothing in particular complained that this was critical of Arabic barbarism — which, of course, was the point of the lyric. Nonetheless, in an early example of the mental pathology placing political correctness above art and honesty, Disney cravenly rewrote the lyric to some meaningless phrase that neither fits the rhyme, nor meter, nor theme.

” Oh, I come from a land, from a faraway place,

where the caravan camels roam.

It is flat and immense and the heat is intense;

it’s barbaric, but, hey! It’s home.”

The edit is jarring, because the singer’s voice changes here for this one line. Intense does not rhyme with face. The meter is changed from a simple ABAB rhyme to ABCCB to force an internal rhyme. The phrase is meaningless because cruel and arbitrary ear-lopping is indeed barbaric, whereas a hot climate in flat immensity is not barbaric.

Keep in mind that neither the flatness nor the heat of the desert is ever once a plot point in the film, whereas the cruelty of shopkeepers, guards, and grand viziers is a major point, recurring throughout the film. Disney altered none of the scenes where beggar children were threatened with a lash by a prince, or a girl with dismemberment for thieving, or any of the other Arabian cruelties. Those were left in. Merely the witty reference to them in the opening song was marred.

This flaw stings me each time I rewatch the film, as the original is out of reach for me. The seed of the downfall of Disney was planted at this time, in this small way. It is indeed a tiny thing to vex an otherwise remarkably enjoyable film, but the thorn, howsoever small, strikes me at a tender spot.

Aside from these very minor flaws, visible only to nitpicking perfectionist, ALADDIN is a classic in every sense of the word, and my recommendation could not be stronger. If you have somehow never seen this, rejoice! Wonders await.