Review BEAUTY AND THE BEAST by Disney

We are reviewing all the feature-length Disney animated films in order. We have now reached the pinnacle, the best film of the Disney Renaissance, the best film of Disney’s portfolio, the best animated film of any animator, the best film ever filmed whether live action or animated.

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (1991) was produced by Howard Ashman, and received lauds and awards it would be tedious to recite, but which were well deserved.

Naturally, I can make no pretense of objectivity when reviewing my favorite film: I can only hope to list the virtues that I imagine even those not infatuated by this film in fairness must admit exist.

For I saw this film in the theater when I was a young newlywed, and had no money for tickets, because I myself was a hulky hairy beast who had just been turned into a handsome prince by the first kiss of my beloved beauty, and every element of this film spoke to some part of my life or another. So it would be an understatement to say I recommend it.

This is also the film that abolished any respect I once had for the Oscar Awards, since the Academy award the Best Picture for that year not to this film — but to a grotesque and gory police procedural of remarkably nihilistic foetor, of which the less said, the better.

As with LITTLE MERMAID, and all the classics of their glory days, Disney here returns to the fairy tale genre for inspiration, rewriting the fairy story of de Villeneuve, and taking elements from the Jean Cocteau film version from 1946 .

Disney freely alters elements of the original, eliminating the wicked sisters of Belle, her brothers, and changing her father from a merchant to an eccentric inventor. The central conceit of the original, that Belle asks for a rose rather than the jewels and gowns craved by her selfish sisters, is missing; and the character of Gaston, a handsome but unworthy suitor for Belle, is introduced as a rival to the Beast, whose origin story is also changed.

In the Disney version, the Beast is cursed by a fairy for his selfishness and inhospitality, and given a time limit — before an enchanted rose withers — after which the transformation cannot be undone.

The unseen servants of the haunted castle (portrayed with such memorable surreal moodiness in the Jean Cocteau version) are here the servants of the prince, like him transformed into candlesticks, clocks, feather dusters, teapots and so on, and form the welcome comedy relief. The comedy here is situational rather than slapstick: the pomposity of the talking clock, the Gallic suavity of the candlestick, the matronly charm of the teapot, the innocence of her son, the teacup.

The film opens with a musical set piece in the finest tradition of the American Broadway musical, introducing Belle as a bookish girl, not well understood in her provincial town, who dreams of wonder in far off places.

We are introduced to Gaston, the handsome and arrogant hunter who has determined to marry Belle, on the grounds that he deserves to wed the fairest lass in the town. His dwarfish sidekick Le Fou is absurd yet charming for his doglike loyalty and hero worship of his master, which we see expressed in a later song.

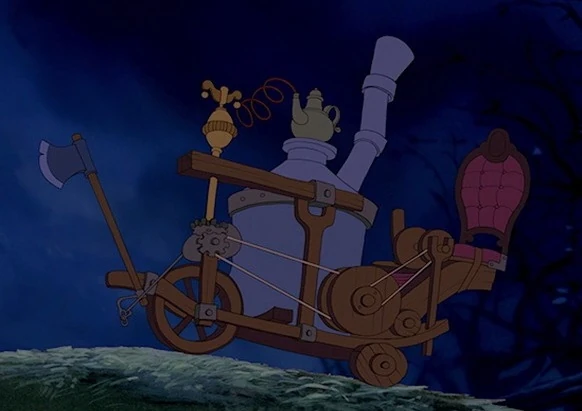

Her father the inventor is a storybook eccentric working on a stream powered chopping machine, which he hopes to take to the local fair.

The father becomes lost in the woods, enters the haunted castle, is entertained by the enchanted servants, but runs afoul of the Beast, who imprisons him. Meanwhile, Gaston proposes marriage to Belle, is thwarted and humiliated. Her father’s horse returns riderless to their cottage, and, at Belle’s urging, returns to the castle with her. Finding her father behind bars, she agrees with the Beast to stay in his place, and to her surprise, the Beast insists she is a guest, not a prisoner.

Unlike in the original, this Beast does not ask for her hand in marriage, nor does she have dreams of him in his true princely form. Instead, her curiosity prompts her into a forbidden room, where the magic rose which holds the Beast’s only hope of breaking the curse is slowly withering, and, terrified by his anger, she flees into the snow, is attacked by wolves, and rescued by the Beast, who is sorely wounded in the fight.

She helps him to return to the castle, and tends his wounds. They quarrel and reconcile, and begin to develop romantic feelings for each other, despite his hideous appearance.

He delights her with his extensive library, they spend time throwing snowballs and dancing. Songs ensue.

Meanwhile, the father seeks help from the villagers, and tells them of the Beast in his haunted castle. He is disbelieved, is mocked, and thrown into the snow. Gaston now conspires against him.

The Beast is now fast friends with Belle, perhaps more, and he discovers she cannot be happy unless she knows her father is well. He provides her with a magic mirror, which allows Bell to see her father is in danger. The Beast gives her the mirror, and releases her to go to the father, falling to despair because his sole hope of breaking the spell is now lost.

Belle finds her father in lost in the snow, and returns to the cottage with him, only to find that Gaston has arranged for the father to be locked in an insane asylum unless she agrees to marry him. She flourishes the mirror to reveal the image of the Beast, proving her father’s story is so, but Gaston in jealousy convinces the townsfolk that the Beast must be hunted down and killed, quoting Shakespeare as he does so.

A fight ensues between animated furniture and terrified townsfolk. Gaston goes alone deep into the castle, finds the Beast, whose despair renders him unwilling to defend himself.

They fight. The Beast prevails, spares the whimpering hunter, who then immediately stabs him in the back. The two totter on the brink of the rooftop. Belle appears, hauls the Beast to safety, lets Gaston fall to his well-deserved death. The Beast dies in her arms, even while she is trying to comfort him.

Too late, she realizes that she loves him. She weeps. Her tears break the spell, resurrect him, and the gloomy castle is restored to glory and beauty in a truly sublime masterpiece of animation. The servants all spring to life as their human selves again.

All live happily ever after, except perhaps for the three Bimbettes, sexy village girls who admired and adored Gaston.

The voice acting is superb. Broadway actress and singer Paige O’Hara does the voice of Belle, and so belts out her songs with haunting grace and girlish charm. One would not think Robby Benson could portray a convincing Beast, and yet he does so with authority, humor, drama, displaying surprising range. David Ogden Steirs (of MASH fame) voices Cogsworth the Butler, Angela Lansbury is Mrs. Potts the teapot, Jerry Orbach is Lumiere the Maitre d’.

Lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken wrote the film’s songs, and there is not a single misplaced note nor unwitty lyric among them. These songs are as brilliant, as easy to sing, as memorable and heartfelt as the best work in the American Broadway musical tradition. Even Disney’s finest film from the classic period might from time to time have an unremembered song or misplaced lyric, but not here. Each song was placed where sound songwriting demands: at the precise moment in the plot when mere dialog is no longer adequate.

Songs added for the sake of stageplays, rereleases, or the blasphemous live action version diminish rather than augment the work, and this indicates that the original achieved perfection. The difference in the tempo and word-cleverness between this and later Disney Renaissance films is audible. If one had no other reason to despise the sin of sodomy, his self-indulgence in this vice robbed us of one of the primary talents of Broadway songwriting ever heard or known. Rest in peace, Howard Ashram. You are missed.

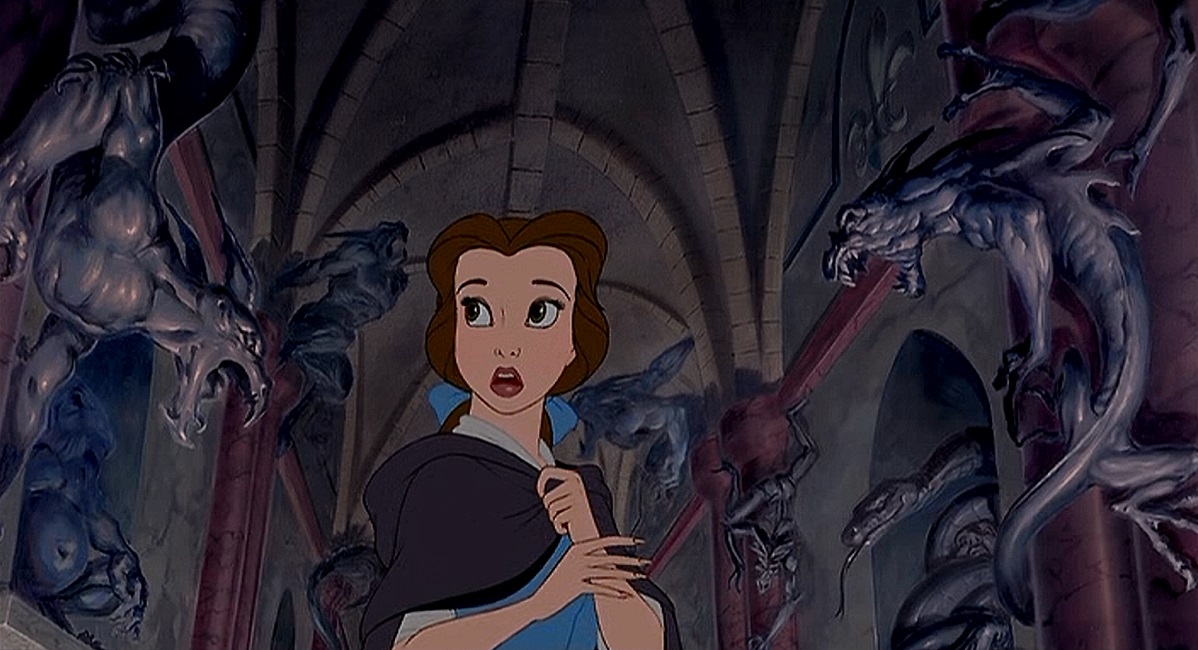

The backgrounds are among Disney’s best. The beauty of the French countryside, the dark menace of the wolf-haunted forest, the grim architecture and gloomy statues of the enchanted castle, are all executed with the perfectionism for which Disney at his best is justly famed.

The animation of the Beast in comedic, tragic, and dramatic moments is carried off convincingly, and he can even be terrifying.

Meanwhile Belle is among the loveliest of Disney heroines, even down to little mannerisms of tucking away a stray strand of hair. It would be unfair not to mention how fetching are the three buxom blonde Bimbettes, and the flirtatious parlor maid.

The look and feel of the background is well done, capturing both the ideal of Eighteenth Century France and of the land of timeless fairytales.

In one or two places, computer-assisted shots of chandeliers or ballrooms might strike the modern eye as unconvincing, but the animation is otherwise expertly done, among Disney’s best.

The theme is held in the very title, for BEAUTY AND THE BEAST contains what perhaps is a Jungian archetype of female romances, namely, that love turns a man from beast to prince.

Disney adds a layer of symbolism atop this with the addition of Gaston, the manly and handsome hunter, who, as an arrogant and boorish philistine, willing to perjure and blackmail to get his way, is discovered to be the real Beast in the tale: in a dramatic moment, Belle says as much in so many words. True beauty is found within.

Gaston’s sin is not that he is boastful—he is actually as skilled a hunter as he says, and he has a swell cleft in his chin, as the song praising him announces. But he is in love with his reflection in the mirror, and, more to the point, is ungrateful. He could have his pick of any of the young blondes in the town, but he only wants the one girl who is not interested in him.

Belle’s bookishness, and her sense of not fitting into her provincial small town is a clever way to provoke sympathy for our heroine, without making her seem petty or proud. Why the father is an inventor rather than a merchant, and why he does not pluck the rose which calls down the wrath of the Beast, is an odd choice at variance with the original, but it helps to explain Belle’s bookishness, and gives an excuse for a comical scene when a stowaway teacup rouses the steam-powered chopping machine to action, to save father and daughter from being locked in a cellar.

Again, I am no fit judge of this film, as it is my favorite film, which found my heart in my life when I was first married, and I myself had just been transformed from beast to prince. There are three other films in my life I might say I admire equally but none I admire more.

The film’s prestige is augmented by following so closely after THE LITTLE MERMAID, which captured much the same magic and Broadway verve, and by preceding ALADDIN and LION KING, also well remembered gems of the Disney Renaissance.

Most highly recommended.