Review THE RESCUERS DOWN UNDER by Disney

We are reviewing the Disney animated features in chronological order.

RESCUERS DOWN UNDER (1990) was released the year after LITTLE MERMAID (1989), but usually is not considered part of the Disney Renaissance: if it is classified as part of the Renaissance films, it has the sad distinction of being the worst box office performer among them.

In theme and style, and poor craftsmanship, RESCUERS DOWN UNDER is more aptly categorized with OLIVER AND COMPANY or THE GREAT MOUSE DETECTIVE, as one of the films of Disney’s lingering the Dry Spell.

Disney famously directed his studio to avoid sequels. This is the sole case among feature-length theatrical offerings where that direction was ignored, and, as it turns out, unwisely so.

Like all Disney films, if you saw it in your youth, it might well be one of your favorites, but when compared with unparalleled greats among the classic Disney offerings, it is not among their best.

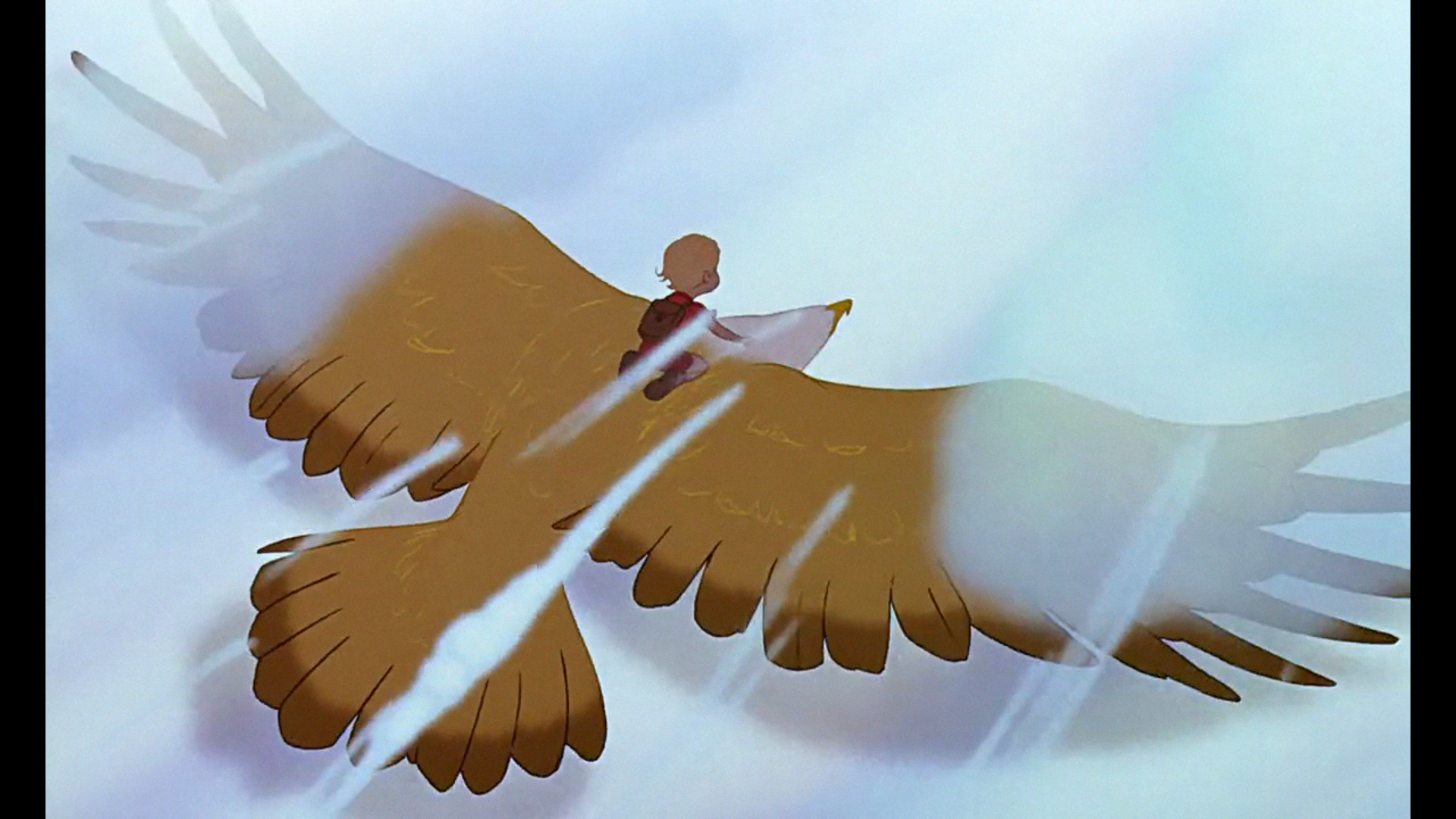

It employs computer animation techniques experimental at the time, and still striking to look at, particularly the scenes of the magnificent eagle in flight, but the film suffers from an unfocused plot, a certain lack of drama, forgettable characters, and an unfortunate abundance of slapstick by the comedy relief albatross.

The story follows the same basic formula of the previous: a child is in danger, and the international organization of rescue mice sends out two of their agents, the elegant Bianca (Eva Gabor) and the shy and self-deprecating Bernard (Bob Newhart), to rescue him.

In this case, the child is an Australian boy named Cody, who rescued and befriended a rare giant golden eagle named Marahute. The child is kidnapped by the ruthless poacher Percival C. McLeach (played with great zest by George C Scott), who hopes to compel or trick the location of the rare bird from him.

To exaggerate the villainy of the poacher, he is revealed to have killed the mate of Marahute, and seeks to smash her eggs, and, by making her the last of an extinct species, to enhance her value.

Meanwhile Bernard seeks to find the nerve to ask Bianca to marry him, but is continually comedically interrupted.

The two travel to Australia on the back of the comedy relief albatross Wilbur (John Candy), brother of Orville from the first film, where they are met by the gallant and competent kangaroo mouse named Jake.

The film cannot seem to decide whether smooth-talking Jake is a romantic rival for Bernard or not. Bernard never actually confronts nor competes with Jake, nor does Jake take any definite steps to win Bianca’s affection, aside from his natural Aussie charm.

Wilbur is wounded during the flight, and taken to a comedy-relief doctor rodent, who terrifies the idiot albatross by menacing him with various chainsaws and deadly implements while he is strapped to an operating table, suffering completely understandable panic attacks. The sequence comes from a horror franchise, but is here played for laughs. Eventually Wilbur escapes. This sequence overstays its welcome considerably, adds nothing to the plot, serves no purpose. Small children of a sadistic bent may find it funny.

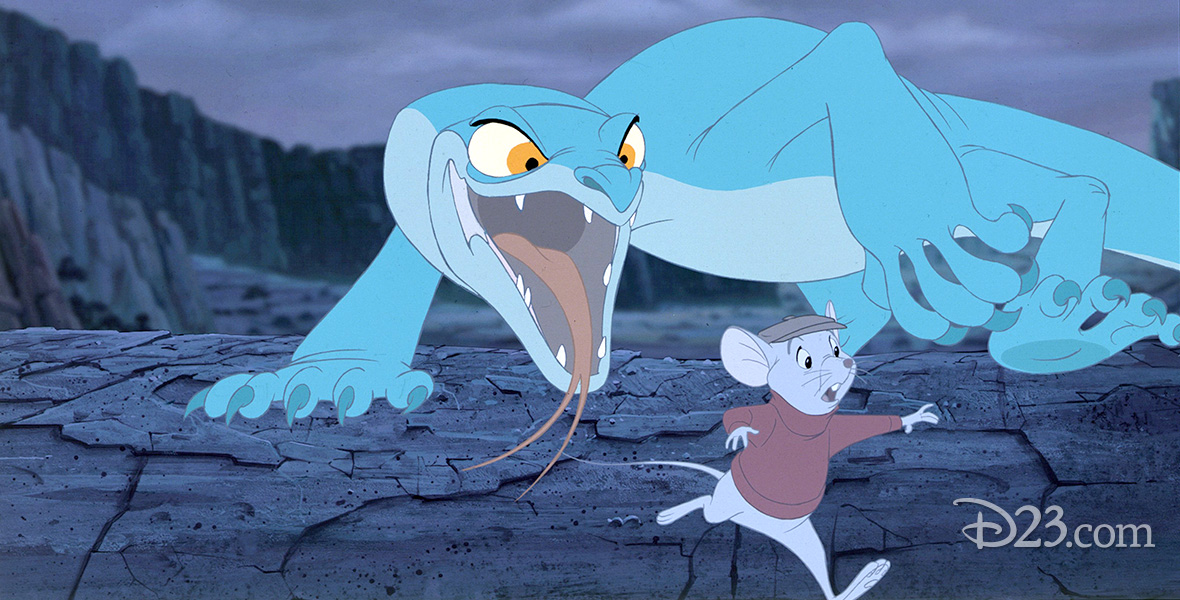

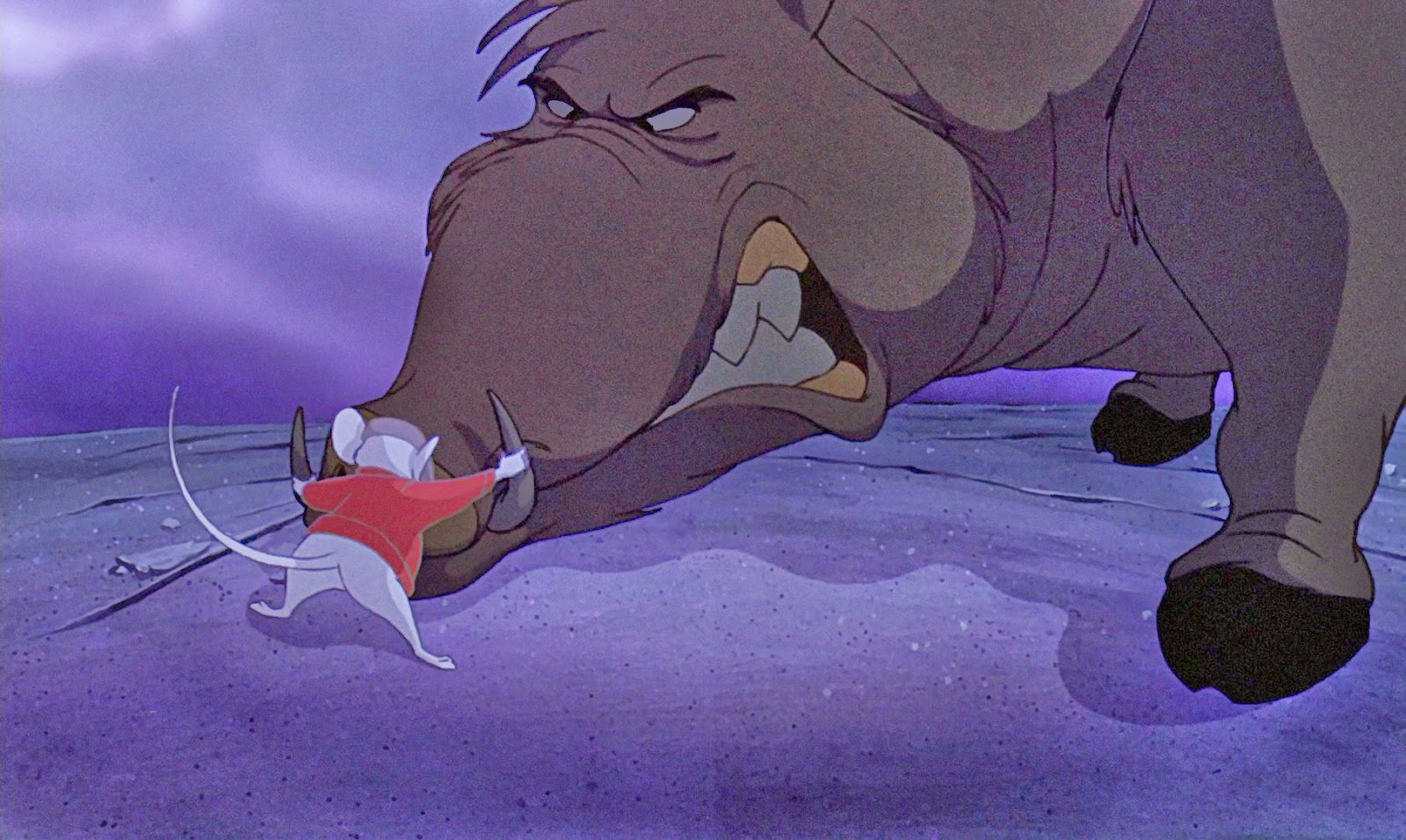

At no point is Jake needed for the plot, aside from hypnotizing a snake by being awesome, a technique Bernard later copies to hypnotize a wild pig into helping him. Unlike the first film, Bianca and Bernard do no detective work, interview no witnesses, and take no real steps to tracking down Cody: he is simply found without much ado.

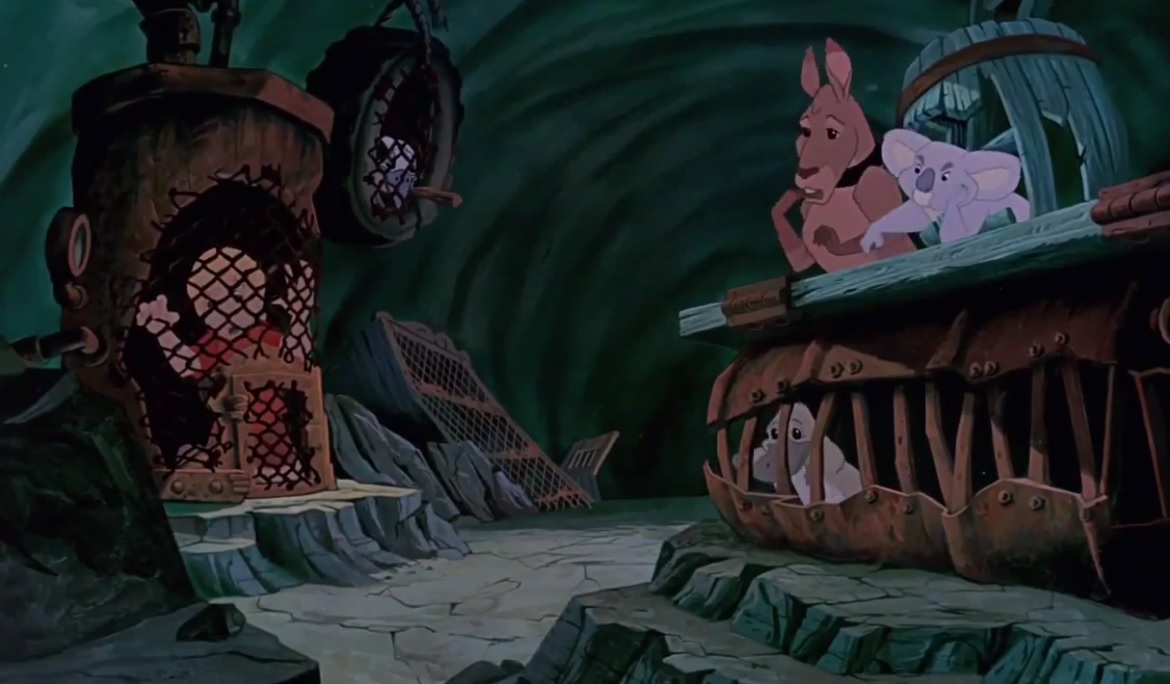

Cody, meanwhile, is thrown into a locked room at the poacher’s hideout with a number of other animals imprisoned by the poacher, and they make several attempts to escape, which are thwarted by Joanna, the poacher’s comedy relief monitor lizard. These fellow prisoners are forgotten in the third act, nor are the repeated failed escape attempts of any interest, because they are both initiated by accident and thwarted by accident, in overabundant spasms of slapstick comedy. The neurotic frilled lizard is particularly annoying, and this audience member merely wished him dead.

The fellow prisoners serve no plot function. Likewise Bianca is not needed for the plot, does nothing, solves no problems, and does not even so much as give a rousing speech to revive the failing hopes of the menfolk. She is imperiled at one point, and Bernard cleverly and heroically rescues her.

Cody is outsmarted by the idiot poacher into leading him to the golden eagle, who is captured in short order. One of two well done plot twists is when Bernard outsmarts the idiot monitor lizard, and saves the golden eagle eggs by substituting them for egg shaped rocks.

Wilbur appears for no particular reason, and is comedically dragooned by Bernard into sitting on the eggs to nurse them to hatching, which saves the endangered species from extinction.

Meanwhile Jake and Bianca, attempting to rescue Cody, are captured by the poacher. So, in effect, Bianca has no role in the plot, and, in the end, neither does Jake.

Bernard hypnotizes a pig into carrying him to the half-track of the villain, where he meddles with the electronics to stall the machine, or, rather, lets himself be chased by Joanna, who by mischance damages the machine.

Meanwhile the poacher takes Cody to the crocodile pool to torture and kill him by suspending him over the waters by a rope, which he then shoots with bullets to part it. By mischance, the poacher and his lizard fall in the water instead, and are swept over a waterfall to their doom. Bernard is not able to rescue Bianca, except he sort of does, by releasing the golden eagle, who rescues Cody and everyone. Bernard proposes, Jake does not seem to mind, the eggs hatch, and all is well in Australia.

The setting is beautifully rendered, the outback drawn with careful craftsmanship. Even tiny details of the Australian animals and architecture are lovingly rendered in the best tradition of Disney perfectionism. Long after the rest of the film is forgotten, the striking appearance of the golden eagle in flight lingers in the memory.

The film is not a musical, which is an unfortunate decision, as this film is sandwiched between LITTLE MERMAID and BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, which won both popular and critical acclaim for the Broadway showtune glory of its music and lyrics, the best Disney ever produced.

I have read other reviewers make much ado over the ecological message in this film, but the message, if it is truly present, if anything, detracts from the film. To be sure, an evil poacher is a stock character in any story starring talking animals, and urging humans not to be cruel to woodland creatures is a longstanding tradition of Disney, not to mention the mainstream of English-speaking children’s stories.

But the simple greed of the poacher here is not as convincing a motive as, for example, the jealousy of the witch-queen in SNOW WHITE or the criminal cupidity of Honest John in PINOCCIO or the lust for revenge of Captain Hook in PETER PAN. The poacher’s desire to destroy the eggs of the golden eagle is simply senseless, considering his willingness to gather and sell other rare animals, of which he has an entire cave full.

The desire to exterminate a species for the sake of rendering the sale value of the survivor is not one a poacher would ever have: the passenger pigeon or the Dodo bird were not wiped out for the sake of being wiped out. It is the motive more appropriate for a villain from Captain Planet, nor a proper Disney villain motivation.

No, if there is a message in this film, it is the same as in Terry Gilliam’s quirky THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN, namely, avoid doctors. No doctors! They are sadistic inflictors of Japanese horror movie levels of pain on innocent cowards and clowns. That message was driven home much more forcefully than any message about saving the dangerous and poisonous critters of Australia.

A second message in the film is: ask your girl for her hand right away.

A third and final message in the film is that Aussies are awesome. Like the Femen of Frank Herbert’s DUNE, life in the ever-dangerous deathscape of the Outback makes men into supermen, and even the kangaroo rats turn into Crocodile Dundee or Steve Irwin. A short visit to Australia allows a mouse to hypnotize a wild pig, and summon animals companions to his aid like a rodent version of Tarzan.

Now, how and why it is that some of the animals talk and others do not, why Cody can talk to beasts like Dr. Dolittle except when he cannot, or why Jake must hypnotize certain animals while merely talking to others is a Narnia-level theological and metaphysical question I am not prepared to answer.

The main weakness of the film, oddly enough, is that it is a Rescuers film. The Rescue Aid Society and its two agents, Bianca and Bernard play no role here that could not have been played just as easily by some animals friends of Cody, who has as much ability to escape on his own, with the aid of the eagle, without any mice to help him — or, if a mouse were needed, Jake the Kangaroo Mouse would have been sufficient.

All in all, this film is not recommended, except, perhaps for the dedicated craftsmanship of portraying the animals and panoramic landscapes, and in particular the magnificent eagle in flight.