Review Disney’s THE FOX AND THE HOUND

I have been watching the Disney animated full length features in chronological order. For most films, this is a revisit to childhood memories, but for two or three of them, which came out in the years between boyhood and fatherhood, this is a first viewing.

As with all Disney films, even the worst of them is someone’s favorite film of all time, for he saw it on that golden afternoon in golden childhood when only the most precious memories are formed. Those who encounter the film only with the cold eyes of adulthood cannot see it as it was meant to be seen, alas.

THE FOX AND THE HOUND (1981) is one such film previously unviewed. I have no young memory of it, and had never heard it discussed by any reviewer. As much as any Disney classic can be, it is obscure. But since it fell in the Dry Spell after Walt Disney’s passing and before the advent of the Disney Renaissance inspired by Howard Ashman, I had a low expectation.

Frankly, I feared, like ARISTOCATS (1970) and ROBIN HOOD (1973) and RESCUERS (1977), the film would be plagued by lax plotting, flat characters, poor animation, dull music, and dumb slapstick which plague the Dry Spell of Disney.

I am very pleased to say that THE FOX AND THE HOUND (1981) that such fear was misplaced. The film does not disappoint, and merits being ranked among the better of Disney offerings. The ending is powerful if sad, and brought a tear to the eye of this cynical old reviewer.

This is perhaps the best film in the Dry Spell.

THE FOX AND THE HOUND is also the swan song of Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, last of the Nine Old Men of Disney animation. They did work on the early stages of character development, and passed the torch to the younger animators who would play a crucial role in the upcoming Disney Renaissance of the next decade. Future directors with a hand in the project included Tim Burton, John Lasseter, and Brad Bird, later of Pixar fame.

It was also at this time that Animator Don Bluth, disappointed with the staleness of Disney, departed to form his own studio, taking nearly a dozen young animators with him. This delayed the production by half a year. The little touches of Don Bluth’s idiosyncratic style visible in the previous film THE RESCUERS are here absent.

The film is based on an award-winning 1967 book of the same name by Daniel P. Mannix, which concerns perennial pursuit of cunning fox by persistent hunting hound as their rural landscape is slowly urbanized, ending in their pointless mutual deaths. Fortunately, this is not a faithful adaptation: nearly all these plot points are reverse or ignored in the Disney version, with only the names being kept the same.

The voice acting is one of the outstanding strengths of the film. One must perhaps be near to my age to recognize the familiar voices of Mickey Rooney and Kurt Russell, Sandy Duncan and Corey Feldman, Pearl Bailey and Jack Albertson, and the great Pat Buttram and the great Paul Winchell (voice of Tigger, Dick Dastardly, Gargamel, not to mention Jerry Mahoney).

The story concerns an orphaned fox cub named Tod (todde is Middle English for fox) saved by a kindly owl and raised by a widowed farmwoman named Tweed. On the same day, her neighbor, the grumpy hunter & fur trapper named Amos Slade brings home a puppy named Copper, for his aging dog Chief to raise and train as a hunting hound. The puppy and the fox cub become fast friends in childhood, playing hide and seek, and vow eternal friendship, despite the natural enmity between the races.

The hunter also has enmity toward the fox after he sees the creature emerge from his chicken coop in a cloud of squawks and feathers, chased by Chief, the older dog. He vows to kill the fox, but for a time, Widow Tweed is able to protect her pet.

The friends are parted for a season when the hound is taken away across the winter to the hills, where he learns the art of hunting and tracking well enough to provoke the envy of Chief, his tutor. Meanwhile the friendly owl warns Todd that Copper is being trained to hunt creatures like him, and that the two must be enemies in the future. He naively vows their friendship will endure.

In spring, now fully grown, Tod tempts fate by sneaking back by night to visit Copper, who is now fully trained and unwilling to disobey his master, Slade, nor his tutor, Chief. The hound in whispers warns the fox they can no longer be friends. Chief wakes and gives chase. The fox is cornered by Copper, but he relents and lets Todd escape.

However, the chase is not over. Chief picks up the trail and chases Tod onto a train trestle. An oncoming train misses the fox and strikes Chief, who plunges down into the vale below, landing at Copper’s feet. Copper, looking up, sees Tod the fox outlined against the moon, and vows revenge.

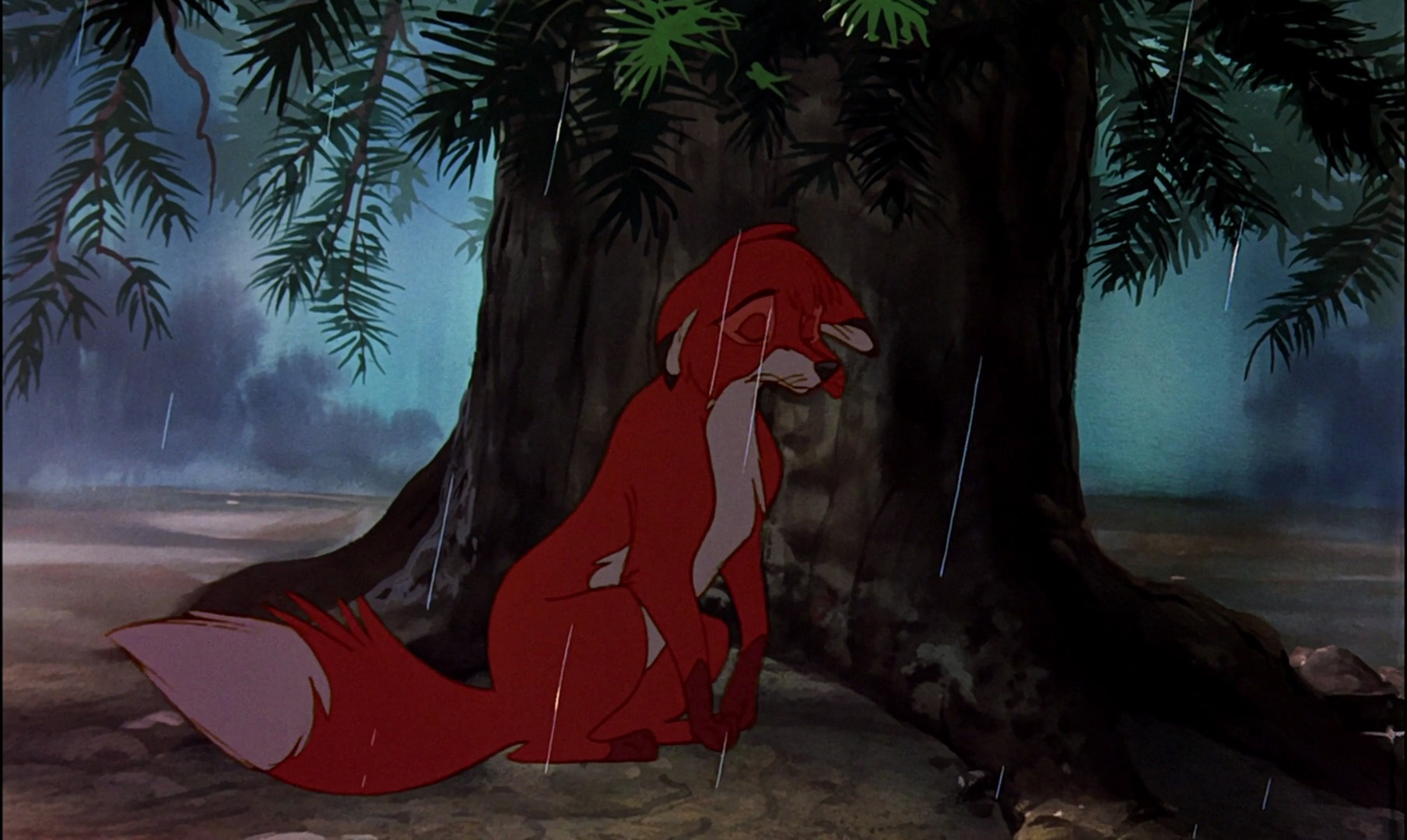

The Widow Tweed realizing she can protect the fully grown fox no longer, after reciting the lyrics of a slow and sad song to herself, exiles Tod to a game preserve, where no hunting is allowed. Tod spends a night of misery in wind and rain, alone and friendless.

The next day he is introduced by the helpful owl to Vixey, a lovely young she-fox, whom he awkwardly woos and wins after a requisite amount of charmingly youthful love-folly. The owl croons a love song and the vixen introduces him to life in the wild. He is sadly not as wary as the vixen raised in the wild, and this leads him into danger.

The pair are beset by Slade and Copper, for the hunter has cut the wire and brought his gun and bear traps to the wild preserve. Tense scenes of walking unwarily amid waiting traps or of being holed up and burned out of a den ensue, remarkably alarming for a Disney movie, and rather dreadful.

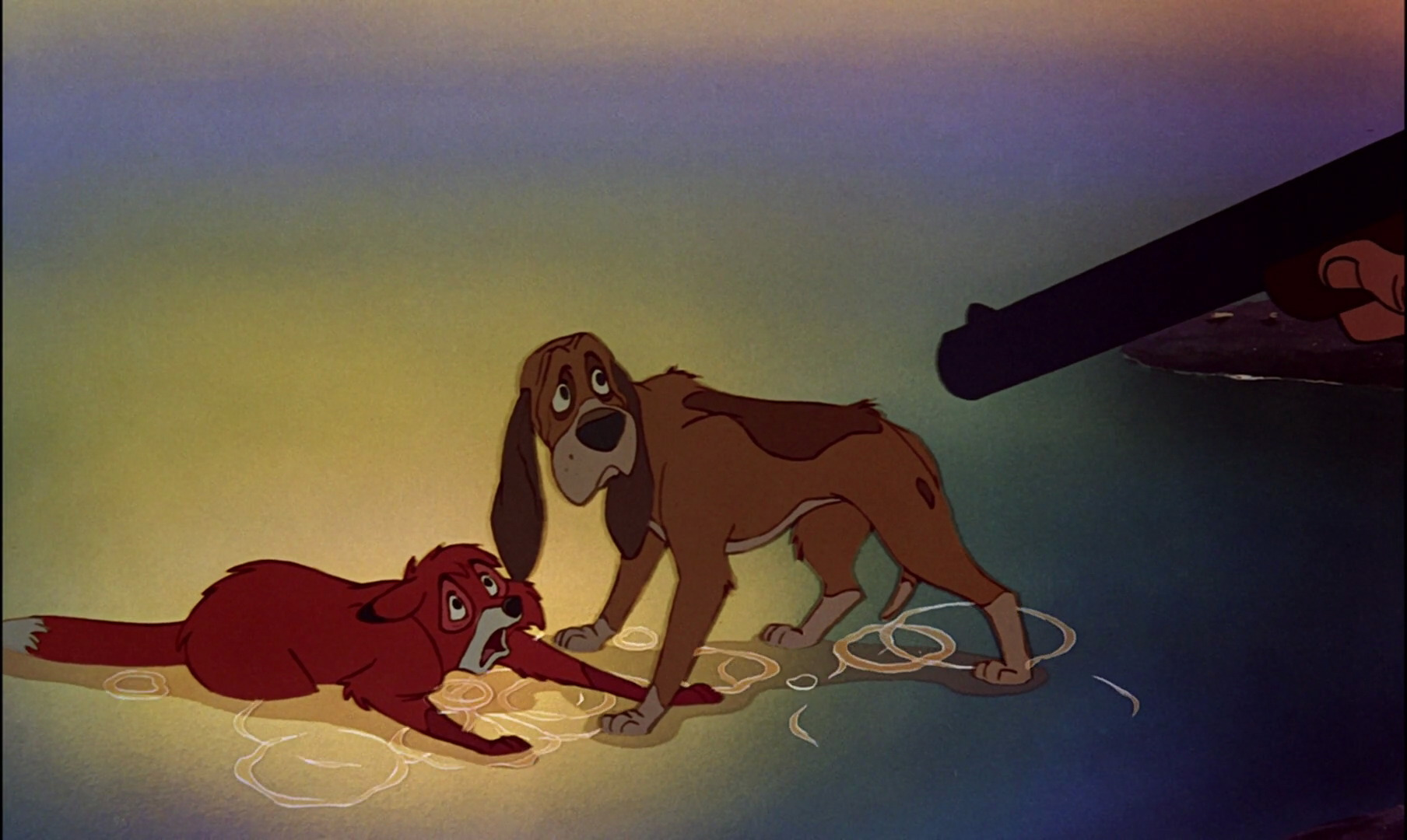

Dreadful as well is the climactic scene when the chase between Copper and Tod is interrupted by a wild bear. The bear attacks Copper. Tod is in the midst of a clean getaway, with Vixey urging him to flee, but Tod turns and savages the bear, hoping to distract the huge monster away from his ex-friend currently trying to kill him. As with Chief, the fox flees to the high ground, this time to a rotting log hanging over a waterfall. It breaks beneath the weight of the bear, but this time Tod is not lucky enough to escape. Down he falls.

I would not dare reveal the surprise ending, nor even say whether it is happy or sad, lest I rob the innocent viewer of the experience. Let me say only that the ending was not what I expected, and even though I knew Disney could not kill off a cute fuzzy main character, I was not sure, and I was right not to be sure. This film stands out from other Disney offerings.

The setting is rural, but the trapper and the farm widow, both equally feisty and trigger-happy, are not portrayed as stereotypical hillbillies. That comes as a refreshing surprise: the portrayal is well rounded and realistic.

Indeed, the main characters are more well rounded than seen in any other Disney films, for the protagonists are flawed, at least a bit, while antagonists are portrayed as sympathetic, at least a bit.

The antagonists Amos and Chief are mean, but that is not all that they are. The antagonist motivations are straightforward but understandable, and, surprisingly, the loyalty between hound and master, tutor and apprentice, was portrayed as positive, even when the master or the tutor was in the wrong. A hound is supposed to be loyal even to a bad master: this is a moral subtlety not normally scene in children’s movies. And in this case, the master is not bad, merely ill tempered.

There was even a scene where the hunter is beset by the bear, and the danger to him is portrayed as fearsome, not comedic. The audience is expected to be on his side at that moment, despite him being the deadly foe of the fox.

Compare this to Maleficent the Evil Fairy, or the Queen of Snow White: these are evil witches with no trace of positive qualities.

That being said, none of thein THE FOX AND THE HOUND characters are archetypal or even particularly memorable. Tod the fox in one line of dialog boasts that he can outfox pursuit, but he is not shown, for example, as being a trickster figure or lovable rogue, as is his fellow fox Robin Hood in the Disney film.

Or when a kindly porcupine offers the fox a den for shelter in the storm during his first night abandoned in the wild, when the voice of Piglet from Winnie the Pooh comes out of his mouth, one is reminded of a much more memorable character, with a strong and clear personality.

Tod the Fox is a nice guy, and so is Copper the Hound, but if the same character were disguised, or was changed by Merlin the Magician into the shape of a bird or fish, he would not stand out. Whereas Piglet or Robin Hood, regardless of any change in shape, would. They have mannerisms and qualities of speech and personality that demark them as individuals. Whereas Tod and Copper do not.

The minor characters share this weakness of being bland but also lack the strength of being well rounded.

We have all seen shows where even minor characters, given only a line or two, display bag-loads of personality, have clear quirks or strengths or sense of humor, and ornament the scene in which they appear, or, at least, find themselves in a secondary plot sequence which serve to emphasize some parallel or contrast with the main plot. Such minor characters have integrity to the story. Here, sadly, despite the small number of parts, one third of the cast could have stayed home with no loss to the storytelling. Why is there a woodpecker in this film?

The music here is bland but serviceable. None of the rhymes nor tunes are particularly memorable, but they are well-placed in the structure of the plot, brief but coming at just the right time, and have an effective emotional impact. I am thinking in particular of the sad song recited, but not sung, by Widow Tweed as she abandons her pet fox in the preserve for his own protection. It is not that good, but it is well executed, and should bring a tear to one’s eye.

The pacing is the weakest part of the film. The editor simply thought the kids needed to see long slapstick sequences of dimwitted birds hunting caterpillars or comical chase scenes where a dog in hot pursuit of the fox pulls a barrel full of squawking hens behind him on his leash, smashing huts and fences and making pratfalls into the creek.

There is likewise an earlier scene with a fox cub startling a chicken in the barn, who upsets a cow to dashing her milk pail, while the widow refuses to stay mad at the fox cub, who did not seem to do anything wrong — one is reminded of several scenes from other films in the Dry Spell, likewise with no point and no payoff.

The simplicity of execution is the strongest part of the film. The opening sequence where the fox cub is orphaned by a hunter shooting his mother, and the final scene where the grown fox is in the gunsites of the wounded and wrathful hunter, have no dialog and no music. Everything is cut to a minimum, and this gives it maximum impact. The tension is made greater by the silence, and we see expressions tell the whole story without a word spoken. It is masterfully done.

The bittersweet tone set throughout the film is unusual for Disney, unusual for any children’s film of the era. With all due respect to Don Bluth, much of Disney in the Dry Spell was indeed stale, but this film was simply not.

However, this film does not match the immortal heights of Disney classics neither from the Golden Age of Walt nor the Renaissance of Ashman.

Most works from the Dry Spell were mediocre films, but peppered with good elements, a single stand out song or scene or character, or perhaps even a great element.

Contrariwise, THE FOX AND THE HOUND is a great film with peppered with mediocre elements.

Worth watching.